An Interview with Yevgenia Nayberg

Yevgenia Nayberg

March 26, 2018

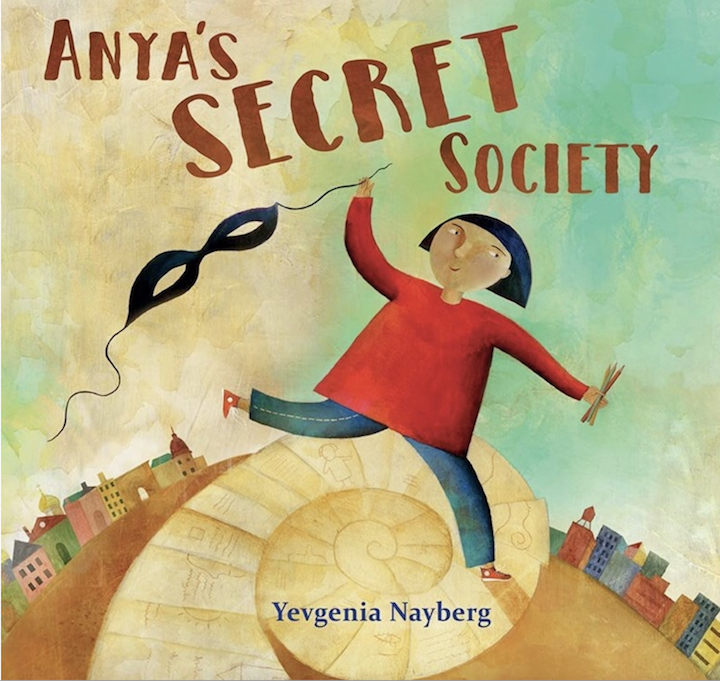

We interviewed Yevgenia Nayberg, acclaimed illustrator and now author of children’s picture books. Her latest books are Anya’s Secret Society, written and illustrated by her and Martin & Anne, written by Nancy Churnin and illustrated by Nayberg. She was originally schooled in art in Russia and her career also includes poster and set design for the theater. She lives and works in New York, creating in her dual fields of theater and illustration.

A Selection of Work

March 26, 2019

You have been described as an artist, a theater designer, an illustrator and now an author. How do you see yourself? Are any of these titles beginning to take a front position? If not, how do you balance these roles?

I feel like it is the same role. You have something to say and you try to say it with the right mixture of clarity and mystery. The medium might be different, but the intention is the same.

Nayberg at work in her studio

Work in progress in Nayberg’s studio

Your Russian schools focused on the technical skills necessary for your art. How has the American approach to illustration style impacted the development of your style?

I was fascinated by the spontaneity of many American illustrators. This is something that I have to consciously cultivate in my work. It takes years to learn technical skills and years to unlearn them.

Cover of Anya’s Secret Society, Yevgenia Nayberg

Like Anya (protagonist from Anya’s Secret Society), you are left handed and although you used your left hand for your art, you were re-trained to write “properly” with your right hand.

I am happy to be ambidextrous in my daily life. Artists in Russia were expected to have a dose of eccentricity. Being able to draw and doing it with my left hand earned me extra points! Anya’s story could be read as a story of a leftie in a right-handed world. But of course, it is just a metaphor for a much bigger challenge—wanting to belong while preserving your individuality.

Work-in-progrees page from Anya’s Secret Society, Yevgenia Nayberg

Interior spread from Anya’s Secret Society, Yevgenia Nayberg

Since living in the United States, what other areas of the country have you visited and what were your impressions?

My first stop in the U.S. was Pittsburgh. I only knew America from Hollywood films and was in for a surprise! After that I lived in Los Angeles for nearly ten years and got to travel throughout the United States for my theatre work. During my years in the U.S. I lost the outsider’s point of view. Today I am happy to call New York City my home—feel the most comfortable and at ease here.

Interior spread from Anya’s Secret Society, Yevgenia Nayberg

Interior spread from Anya’s Secret Society, Yevgenia Nayberg

As you balance the people-oriented theater work with the more solitary task of illustration and writing, do you try to go back and forth to keep from being overwhelmed by either discipline?

I like to mix it up. I am a very social person and love to collaborate with creative allies. At the same time, I am headstrong and tend to know exactly what I want, so solitary work often comes to the rescue!

Interior spread from Anya’s Secret Society, Yevgenia Nayberg

Do you use your sketchbook for preliminary work on specific projects or carry it with you often to draw during your daily commutes or travels?

I don’t have a well-organized sketchbook practice. Most of my sketches are done on the back of document printouts. I am usually self-conscious about sketching in public and often must rely on my visual memory to reconstruct what I saw. Still, I would like to train myself to carry a sketchbook with me more often, because live drawing takes me out of my familiar stylization.

From Nayberg’s sketchbook

From Nayberg’s sketchbook

From Nayberg’s sketchbook

From Nayberg’s sketchbook

What response is most meaningful to you when people view and/or read your work? How do you go about achieving that?

I am not worried about creating a clear road map to my work; I like to leave enough space for the imagination of others. It’s exciting when people see something in my work that I had not planned for!

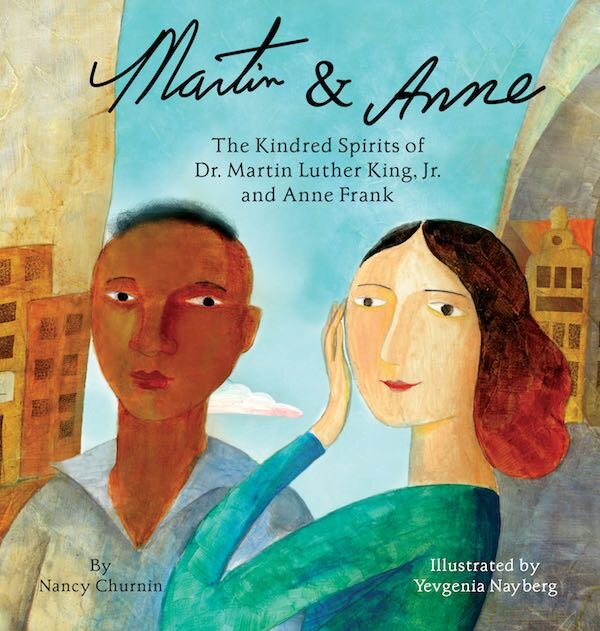

Cover of Martin & Anne: The Kindred Spirits of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Anne Frank, by Nancy Churnin, illustration by Yevgenia Nayberg

Interior spread from Martin & Anne, by Nancy Churnin, illustration by Yevgenia Nayberg

Interior spread from Martin & Anne, by Nancy Churnin, illustration by Yevgenia Nayberg

Did you conduct any special research during the creation of illustrations for Martin & Anne? What challenges did you encounter in illustrating this text written by another author?

I researched the photographs of Frank’s and King’s families quite extensively. I also researched the civil rights movement, the protest posters and the racist and antisemitic signage of that time. I looked into the original edition of Anne Frank’s diary, because it is mentioned in Nancy Churnin’s story. My illustration style is not realistic, and I feel that historically correct details help to ground the artwork.

Interior spread from Martin & Anne, by Nancy Churnin, illustration by Yevgenia Nayberg

Interior spread from Martin & Anne, by Nancy Churnin, illustration by Yevgenia Nayberg

It is probably more challenging for an author to come to terms with an illustrator’s interpretation of her work. In any story that I take on I find something personal and make an intimate connection. After that, it’s easy—it becomes my story.

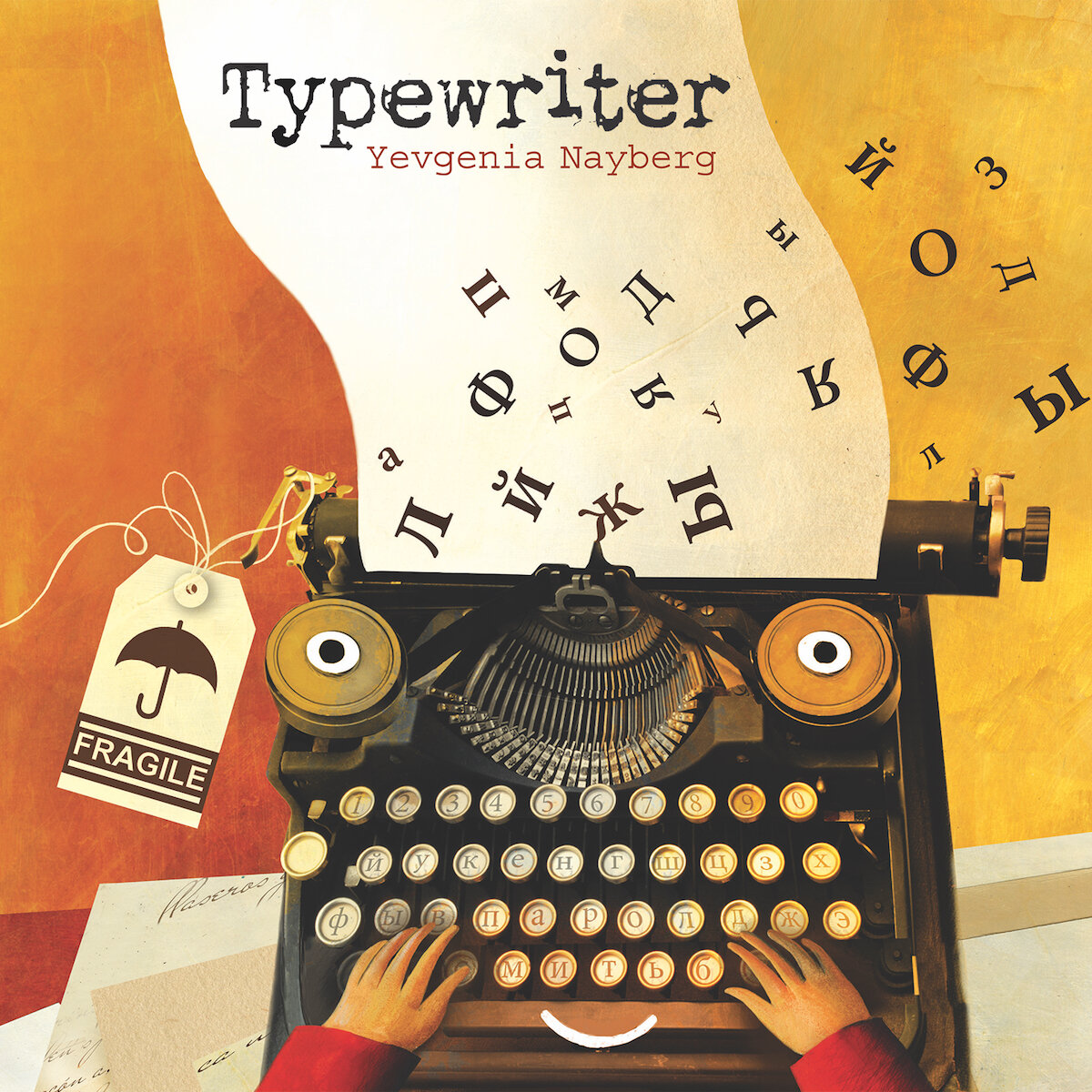

Can you share a little about your upcoming book, Typewriter? Where did this idea come from?

For years I’ve been interested in objects that immigrant families brought to America. Many of those things turned out to be completely useless. Last year, I asked people on Facebook to share their useless things with me. I asked not to tell me about the tomes of Dostoyevsky, matryoshka dolls, or samovars. I was looking for something unusual, but not sentimental. Naturally, I got many responses with Dostoyevsky and the samovars anyway. But there were a few real surprises, including a typewriter with a Russian alphabet. I thought that one cannot come up with a more useless object!

Work-in-progress illustration from Typewriter, Yevgenia Nayberg

Preliminary sketch of interior spread from Typewriter, Yevgenia Nayberg

Interior spread from Typewriter, Yevgenia Nayberg

I wrote and illustrated a story of a Russian typewriter that emigrates to America and, once there, feels completely useless. Russian stories often end badly, but maybe this time around there could be a happy American ending.

Work-in-progress illustration from Typewriter, Yevgenia Nayberg

Work-in-progress pages from Typewriter, Yevgenia Nayberg

Thank you, Yevgenia, for the behind-the-scenes look into your process and your work.

For more on Nayberg:

All images used with permission from Yevgenia Nayberg, Charlesbridge and Creston Books.