An Interview with Guridi

Guridi

July 17, 2020

We interviewed Raùl Guridi, award-winning children’s book illustrator and author. In 2018, Guridi received a Special Mention for the Bologna Ragazzi Award for best picture book for Dos Caminos. His background in graphic design, painting, and advertising changed in 2010 when his focus shifted to writing and illustrating for children’s picture books. He lives and works in Seville, Spain.

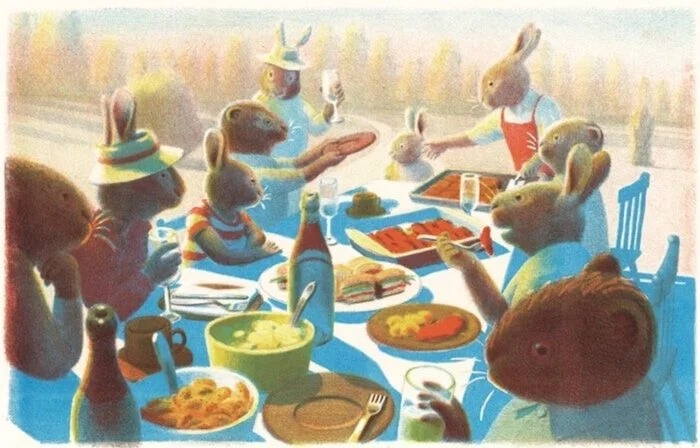

A Selection of Work

Cover of Once Upon a Time, Guridi

Your father was a draftsman and mother a painter. Did growing up in that household expose you to more than the usual amount of art supplies, tools and perhaps inspiration?

Of course. There were desks with pencils mixed with rulers, paints and charcoal, with ship drawings and models. But even without this influence, I may have developed my creativity, because I was a very restless child. My brother was a perfectionist in everything he did, while I was sloppier, always trying different techniques without concern for results.

Interior page from Once Upon aTime, Guridi

Interior pages from Once Upon aTime, Guridi

Although you initially had a background in painting and graphic design, at the Academy of Fine Arts in Seville, in 2010 you turned to illustrating children’s books. Why did you make this transition in your work and career?

Well, I’ve taken a few turns in my professional life, from design to multimedia, to advertising and finally painting . . . but these media were really limited in one aspect or another, or exclusively targeted to direct, fast messaging. Illustration enables a more deliberate vision, a narrative that invites the viewers to become readers of images, while suggesting stories that intertwine with their own personal histories. On the other hand, as a professor, I found myself with no way out, confronting a generation of young people who lacked imagination, full of fear, and unable to create fantasy, which really affected me. I started thinking that illustration, illustrated volumes, would help future generations understand reality through fiction.

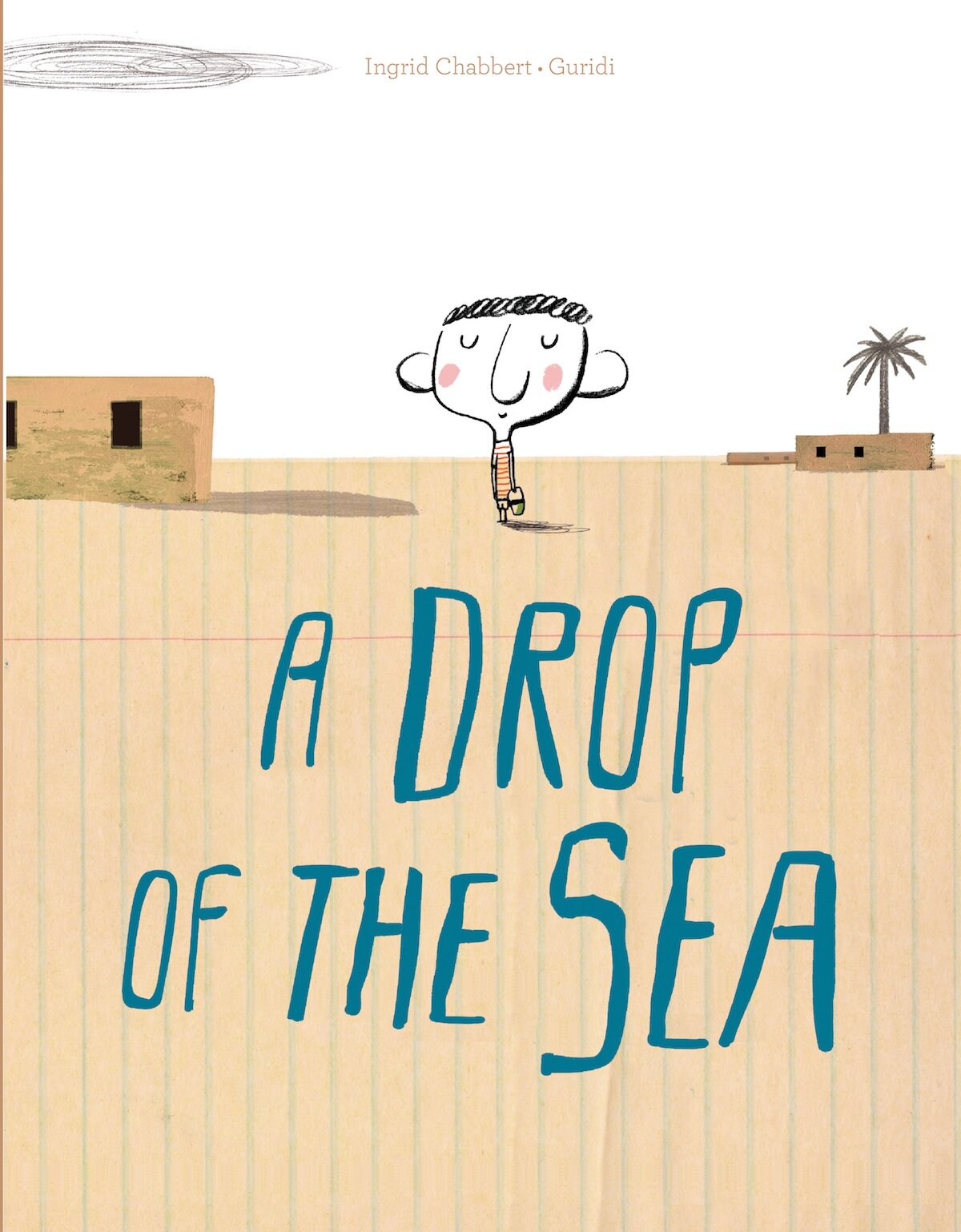

Cover of A Drop of the Sea, by Ingrid Chabbert, illustration by Guridi

We note how important the use of negative space is to the layout of your pages. Do you feel that your early graphic design training contributes to the resulting style in your illustrative work?

Possibly. When I draw, or rather, when I create a scene, I always think about the reader’s gaze. Like a stage when the curtain opens and all elements are there, waiting to tell a story with the space between them. Now more than ever, we are aware of the concept of interpersonal space and its significance. In design, text and image are the same thing; each character, each typography, each element must be in its place, its space; knowing how to play with this is crucial in order for the message to come across. It’s like an architecture of words, lines and color.

Interior spread from A Drop of the Sea, by Ingrid Chabbert, illustration by Guridi

Interior spread from A Drop of the Sea, by Ingrid Chabbert, illustration by Guridi

Interior spread from A Drop of the Sea, by Ingrid Chabbert, illustration by Guridi

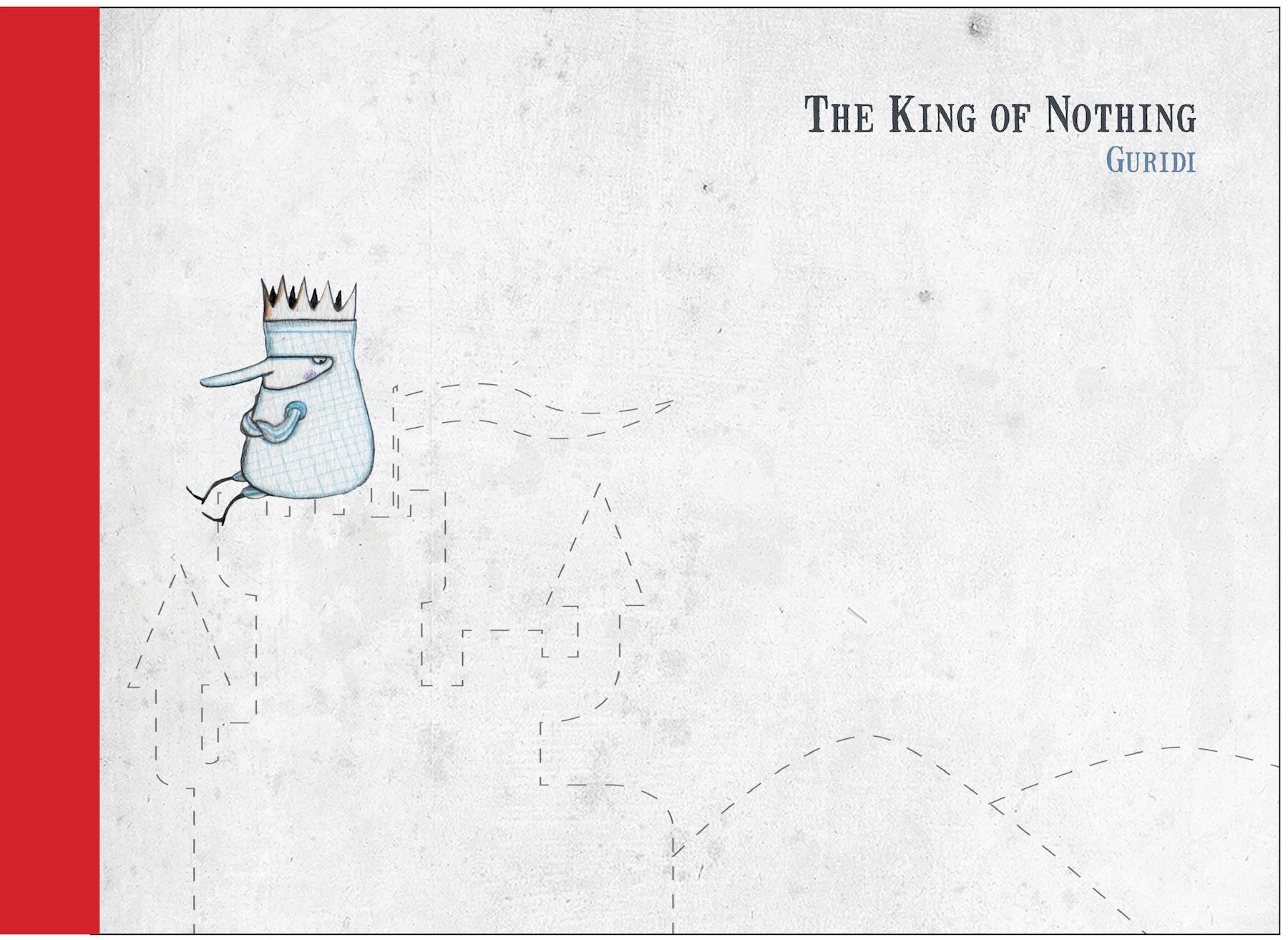

Cover of The King of Nothing, Guridi

Interior spread from The King of Nothing, Guridi

Interior spread from The King of Nothing, Guridi

What drives your style of limited use of color in your work?

Color is the first thing we perceive, even before shape, and that distracts from meaning. Children are taught to “color” by filling shapes with it, without giving it the importance it deserves. In my case, color is one more element, one that offers symbolism, which plays with the image’s subjectivity. I’m more about strokes; perhaps I like the emotion they create, their imprint; color always comes later to tell its parallel story.

Cover of King of the Castle, by Aurora Ruá, illustration by Guridi

Interior spread from King of the Castle, by Aurora Ruá, illustration by Guridi

Interior spread from King of the Castle, by Aurora Ruá, illustration by Guridi

Do you have an interest in exploring other media that would be a departure from your existing body of work?

I do it all the time, maybe too much, not because I get tired of the media I use, but rather because I like to explore art’s possibilities in all its manifestations. I rarely control any medium 100%, except drawing, but maybe that lack of control is what allows for chance, a close friend of success in art.

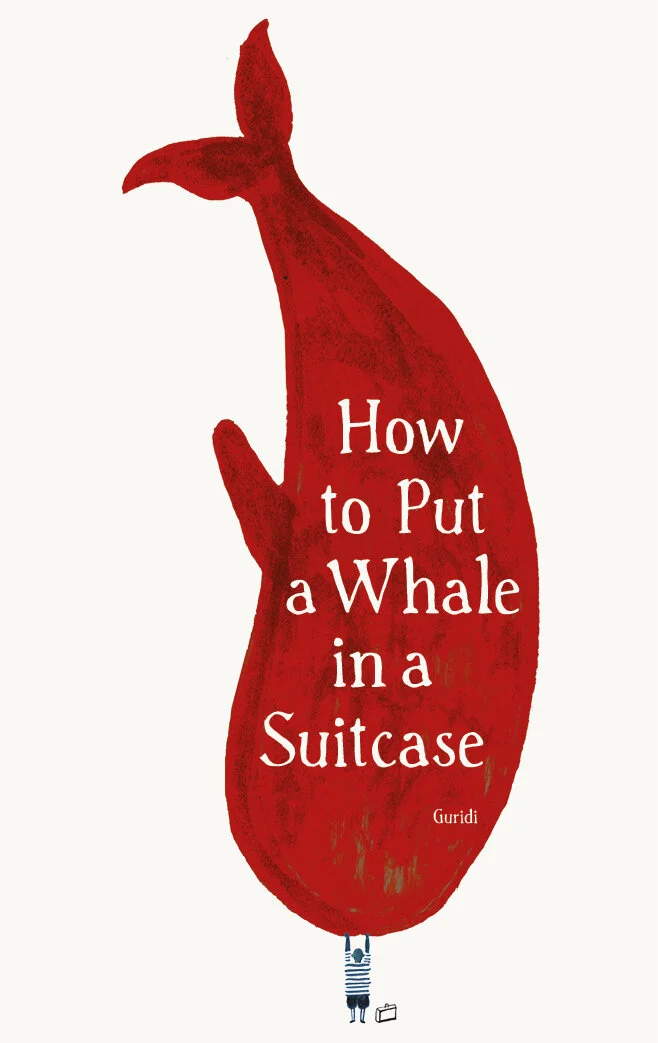

Cover of How to Put a Whale in a Suitcase, Guridi

What led you to write and illustrate How to Put a Whale in a Suitcase?

The West has a lack of knowledge of what happens in other countries, partly out of complacency, but also due to misinformation, especially regarding migration crises. We live in a time in which borders are being closed like never before, in which we use and replete other countries’ resources, and when they do not have enough to survive, we let them die carelessly. This book should help us take off the mask, become citizens of the world, put ourselves in a suitcase and see what happens when our imagination is all we have left from the gaze of a child who runs away and doesn’t know why. This is a vindicatory book, a direct message to the heart, if we have any left.

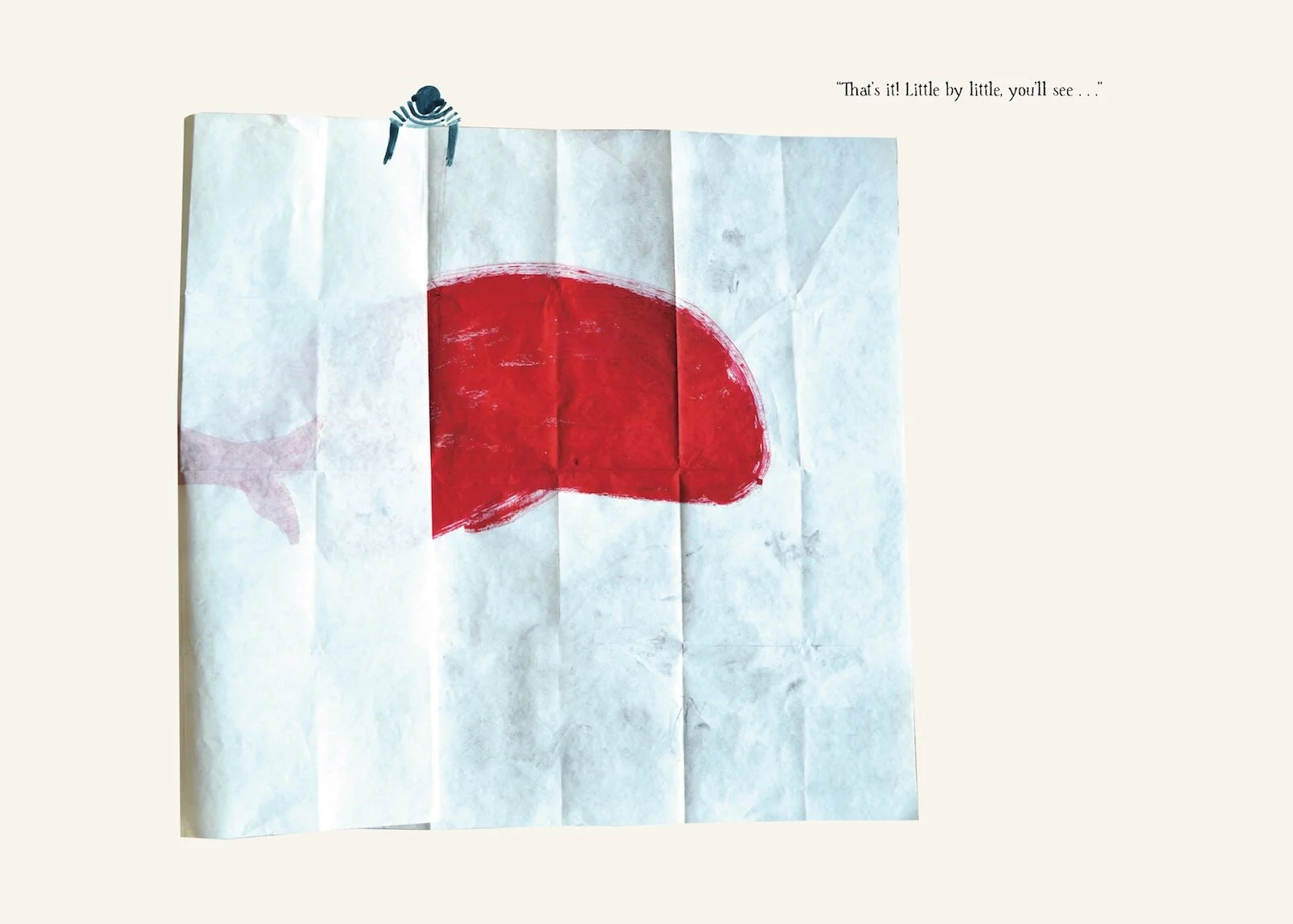

Interior page from How to Put a Whale in a Suitcase, Guridi

Interior page from How to Put a Whale in a Suitcase, Guridi

Do you ever feel the translation of one of your books into English (or any other language) causes it to lose some of the meaning you originally intended with your own words?

Perhaps with one or two titles, but overall, they are really respectful. We also must take into account that cultures are different, so certain expressions are different. I like to see how idioms adapt to each language, I think it is an enriching experience overall.

Interior page from How to Put a Whale in a Suitcase, Guridi

Your books often touch on large themes: the environment, immigration, etc. We applaud that. But these can be challenging subjects to present to young children. What about your approach, do you think, makes these sensitive and important issues understandable to your younger readers?

I hope so. For me, these are essential themes, these books are essential, not only because they entertain, but also because they make readers think, see a different perspective. Individuals who read are usually more open and young people should read more, not in order to know more, but to have more points of reference and a critical and auto-critical approach. The illustrated volume is the perfect genre because it allows many possible readings and allows the reader to become a part of the story. Perhaps that is its revolutionary spirit—the universality of the reading. I like to think that I just put the themes that I care about, that we care about, on the table.

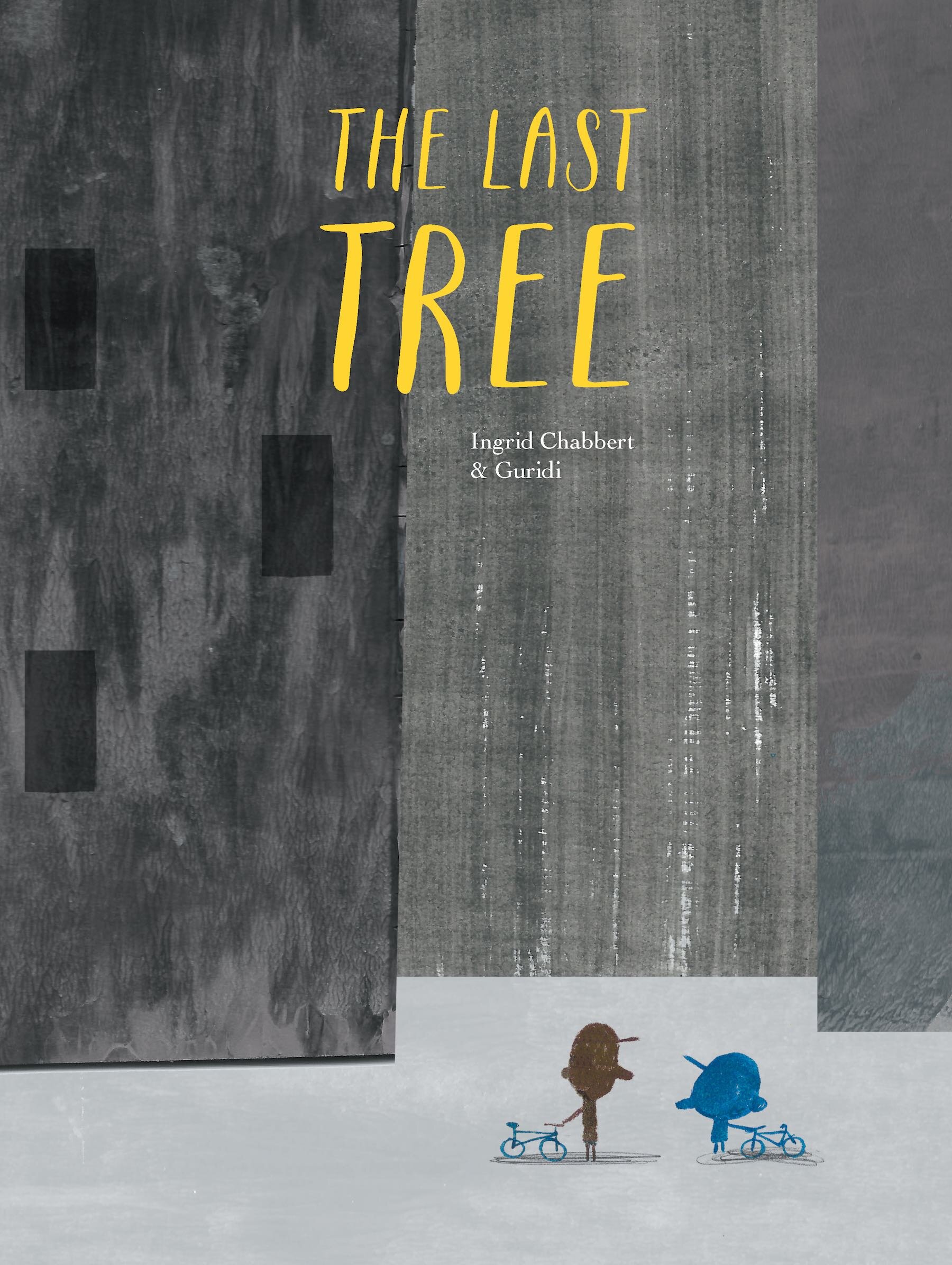

Cover of The Last Tree, by Ingrid Chabbert, illustration by Guridi

Interior spread from The Last Tree, by Ingrid Chabbert, illustration by Guridi

Interior spread from The Last Tree, by Ingrid Chabbert, illustration by Guridi

Interior spread from The Last Tree, by Ingrid Chabbert, illustration by Guridi

Do you believe the world of children’s literature sometimes underestimates the depth of topics that young children are capable of understanding?

Of course. The majority of children's literature has an entertainment purpose and I believe that’s a mistake. I’m not trying to say that all books should have a message or make you think, but rather that a book is a living thing that has more significance because it is shared and interpreted. The problem is that children are left to read alone, rather than reading with family members. If you ever attend a reading session with a narrator and you get to see the children’s and parents’ faces, you'll see what I mean.

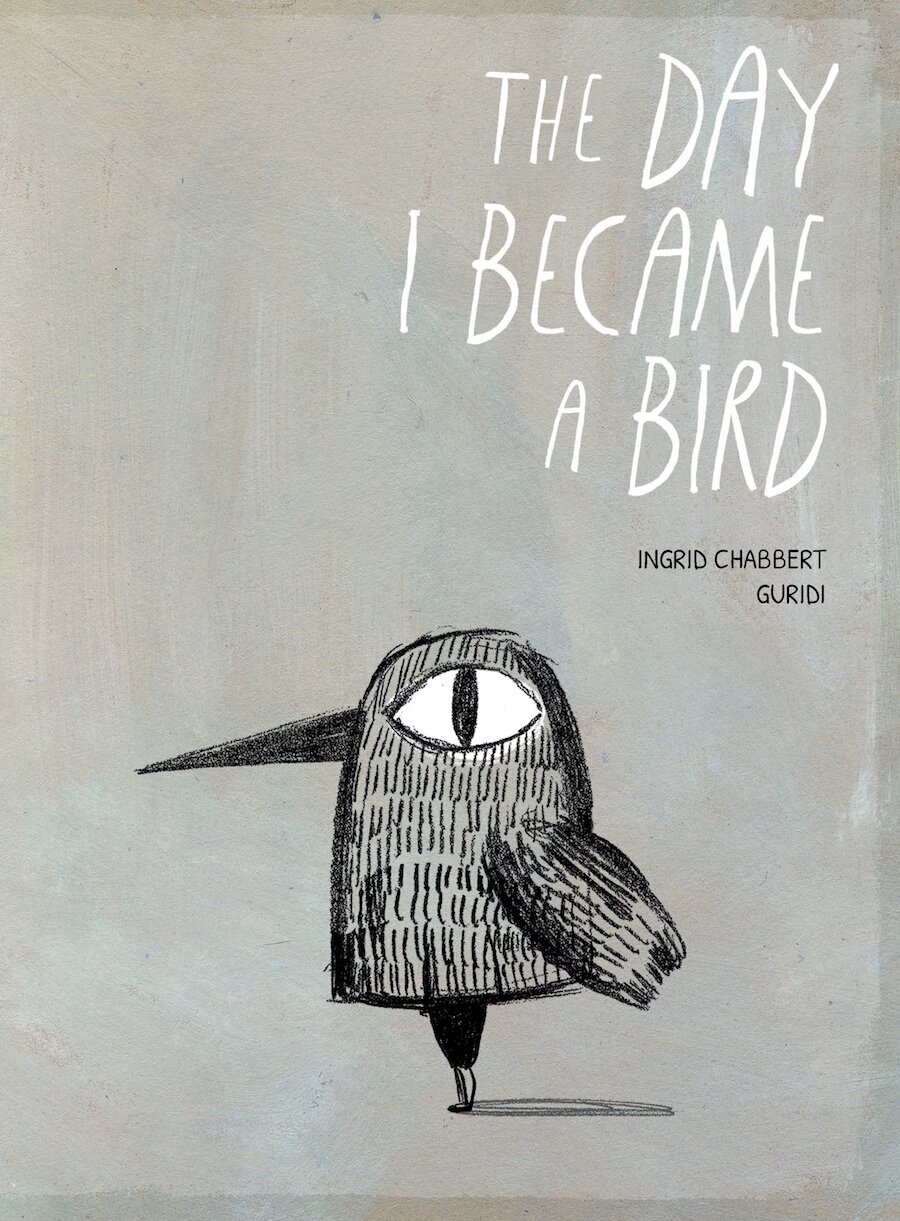

Cover of The Day I Became a Bird, by Ingrid Chabbert, illustration by Guridi

Interior spread from The Day I Became a Bird, by Ingrid Chabbert, illustration by Guridi

Interior spread from The Day I Became a Bird, by Ingrid Chabbert, illustration by Guridi

Interior spread from The Day I Became a Bird, by Ingrid Chabbert, illustration by Guridi

Do you keep an on-going sketchbook? If so, please describe how you use it: as an idea notebook, a drawing practice?

I have many. I’m passionate about them and they’re usually a mixed bag. You may find the grocery list, a storyboard, a sketch of one of my children, paper scraps, etc. . . . For me, sketchbooks are a second brain, the fingerprint of my process and a reference I can revisit again and again during the creative process. I don’t show special respect for each specific page; my sketchbooks may be torn, handled and dirty, but they are filled with chances and opportunities for new projects. They are a catalog of beginnings.

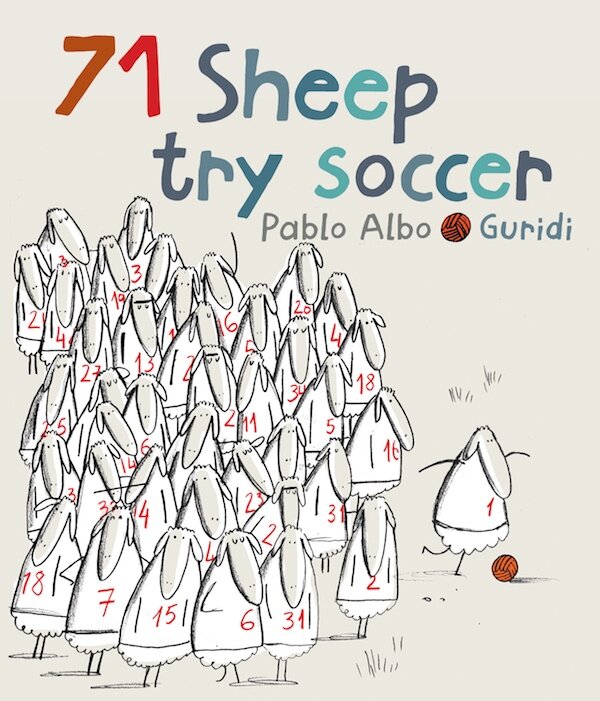

Cover of 71 Sheep Try Soccer, by Pablo Also, illustration by Guridi

Interior spread from 71 Sheep Try Soccer, by Pablo Albo, illustration by Guridi

Interior spread from 71 Sheep Try Soccer, by Pablo Albo, illustration by Guridi

What was your favorite book as a child? Were you an avid reader?

I didn’t use to read many books, but would read a lot of comic books. My first book was Frankenstein.When I read it, every sentence by Mary Shelley, every scene I recreated in my mind, fascinated me more and more. The myth of Prometheus, that constant desire to give meaning to our existence, the need to have someone to share moments with, research, biology and the study of life . . . It’s such an essential book to understand so many things.

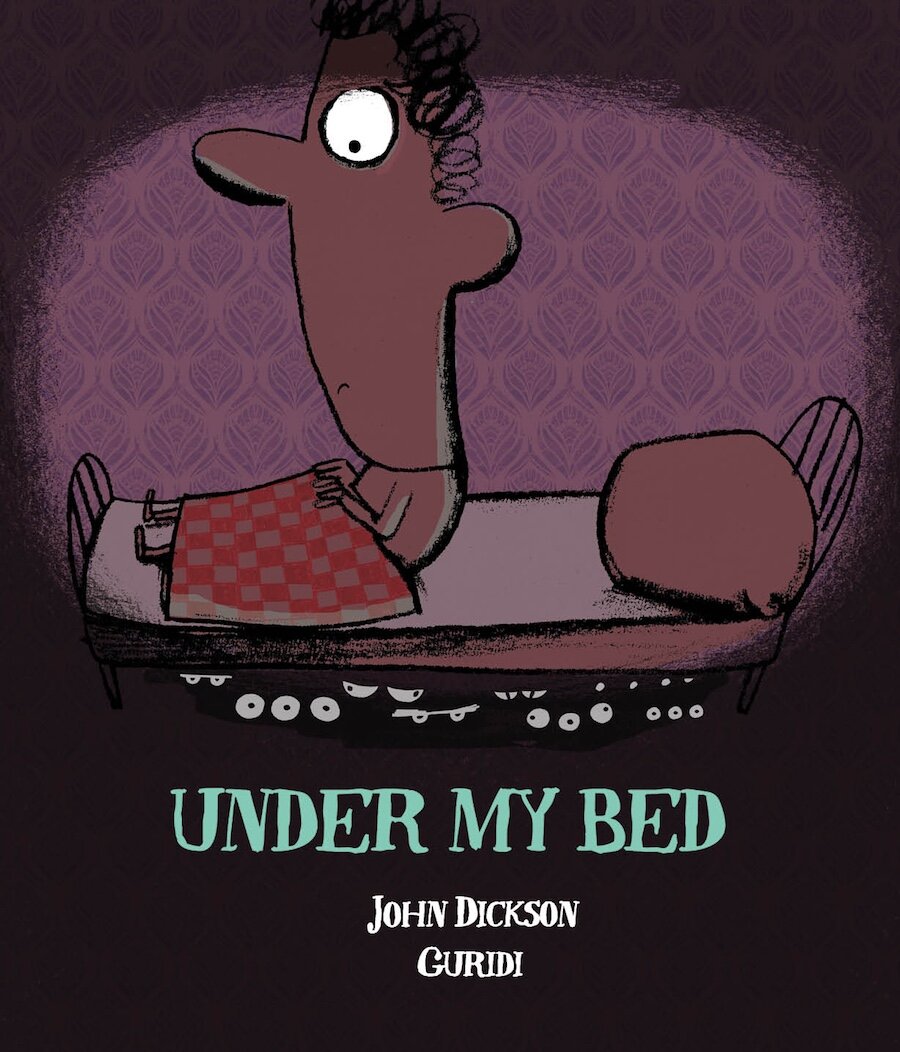

Cover of Under My Bed, by John Dickson, illustration by Guridi

Interior spread from Under My Bed, by John Dickson, illustration by Guridi

Interior spread from Under My Bed, by John Dickson, illustration by Guridi

Thank you for giving us a look at your creative process and work.

All images used with permission from Guridi and Abrams Books for Young Readers, Berbay Books, Kids Can Press and Tate Publishing.

Translation from Spanish of interview by Teresa Fernandez, Ph.D.