An Interview with Isabelle Arsenault

Isabelle Arsenault

February 9, 2020

We interviewed Isabelle Arsenault, award-winning illustrator and author of children’s picture books. Among her numerous honors, she has been included in New York Times 10 Best Illustrated Books of the year three times. She is also a three-time winner of Canada’s Governor General’s Literary Award. She lives and works in Montreal, Canada.

In your work, do you continue to use a loose style of layout and illustration in the preliminary stages when you begin a new book?

Yes, always. Whenever I start a project, I like leaving my options as wide open as possible for whatever lies ahead. I approach the subject intuitively, trying to capture the tone, the voice, the mood of the piece without too much precision. At this stage I don’t want to spend too much time on the details—I prefer pacing myself for later. Moreover, defining the project from the get-go weighs it down. Keeping it broad leaves room for the project to evolve and experimentation later on. I like to leave a few doors open so as not to feel restricted when working on my final renders. In these final stages I’m still leaving a significant space for improvisation, elements of surprise and the unexpected.

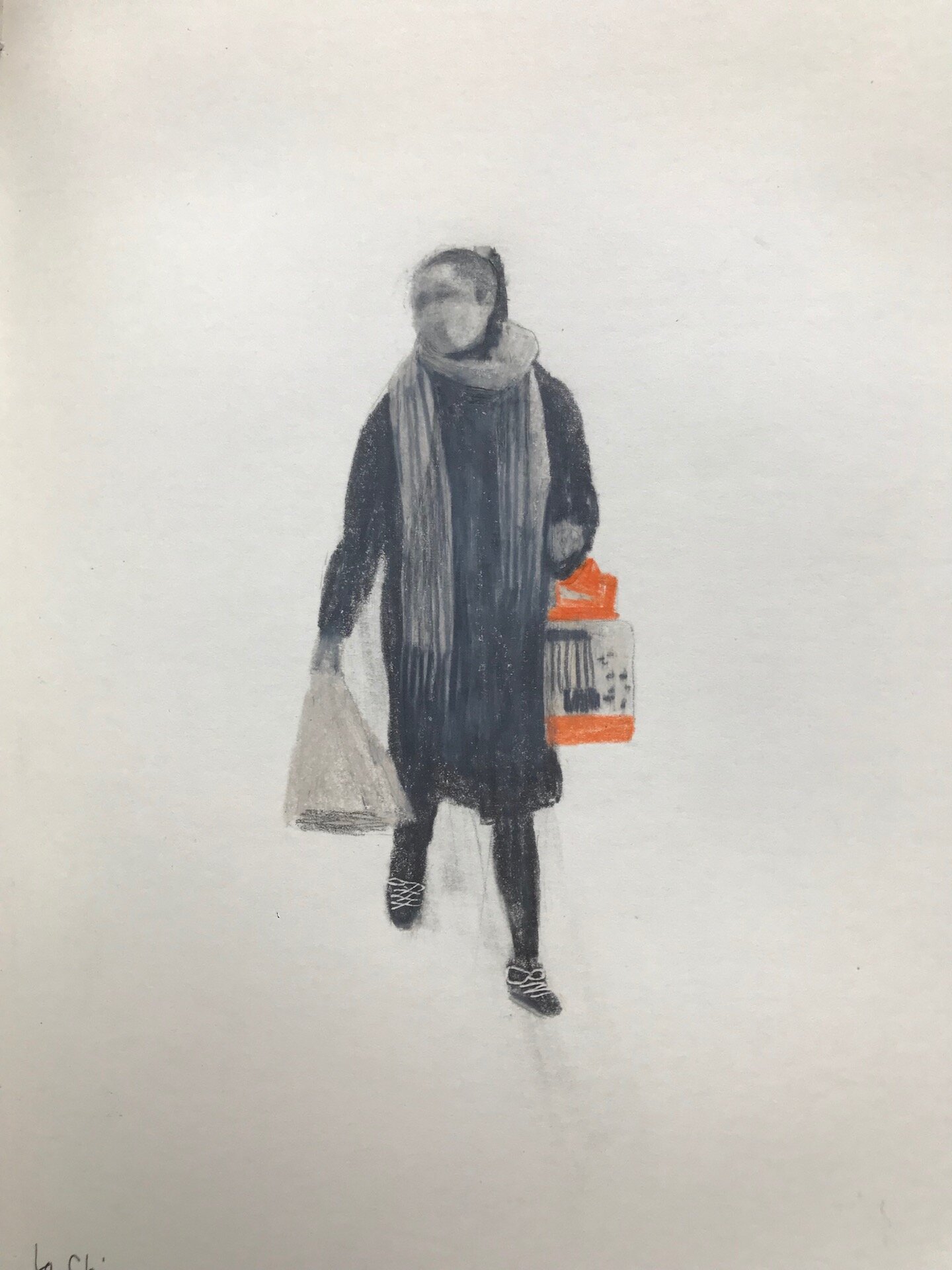

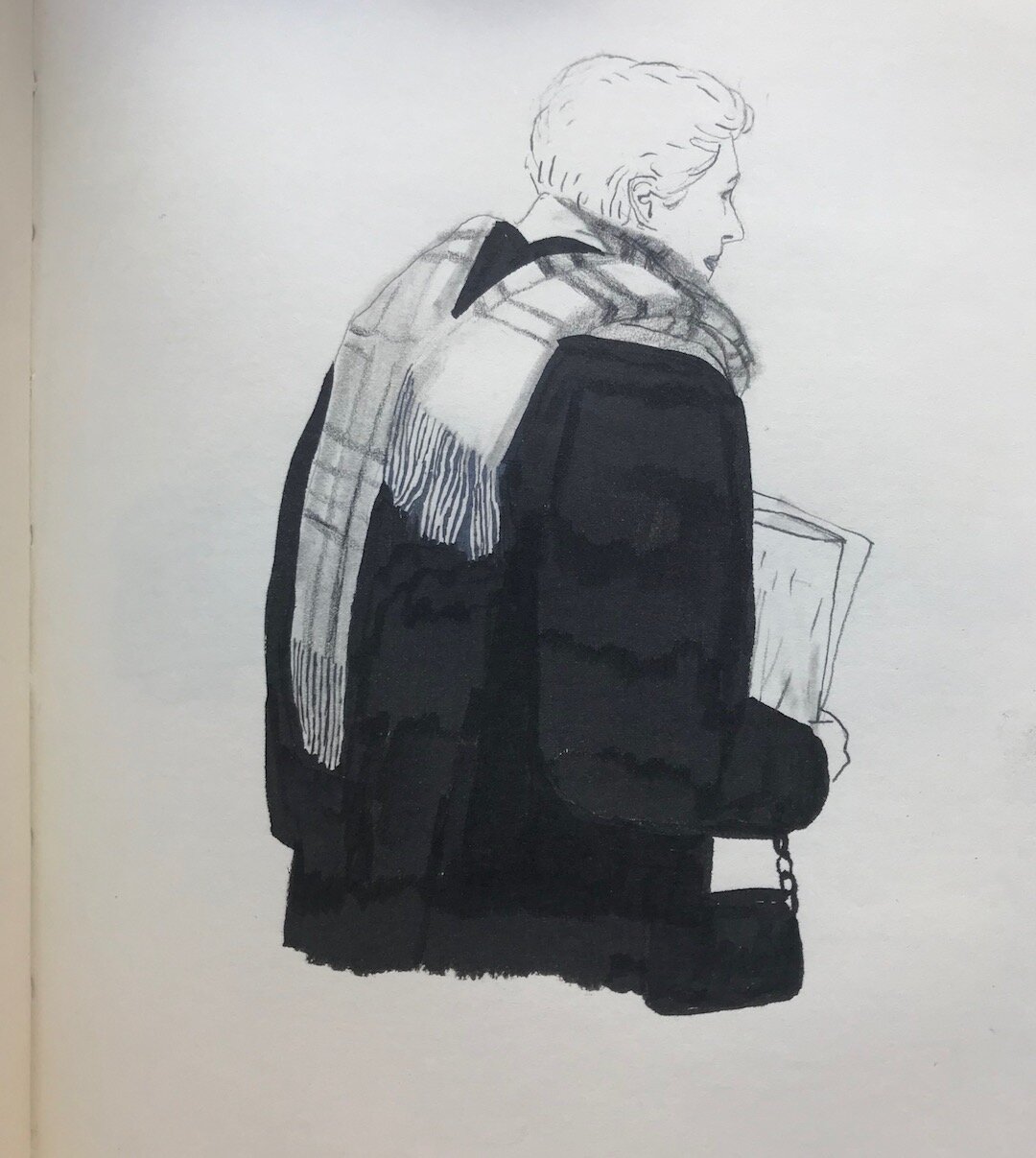

Preliminary work by Isabelle Arsenault from Jane, the fox & me

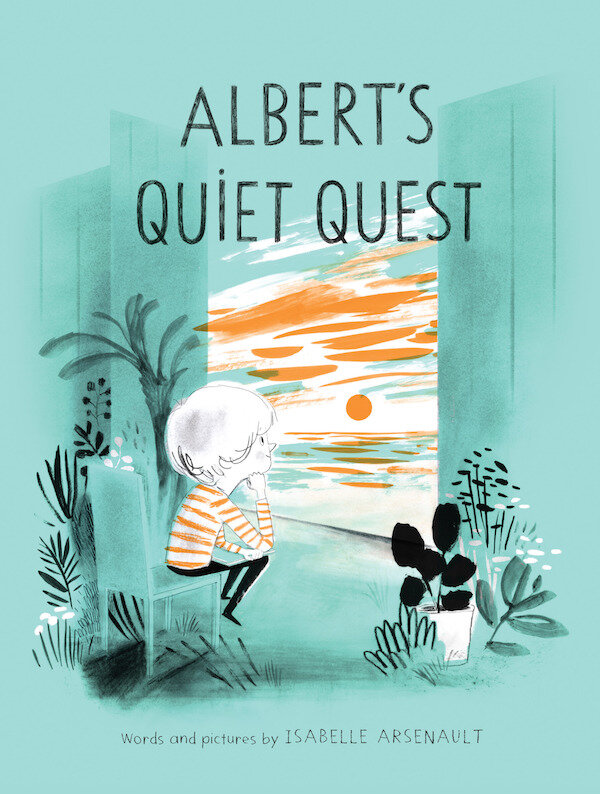

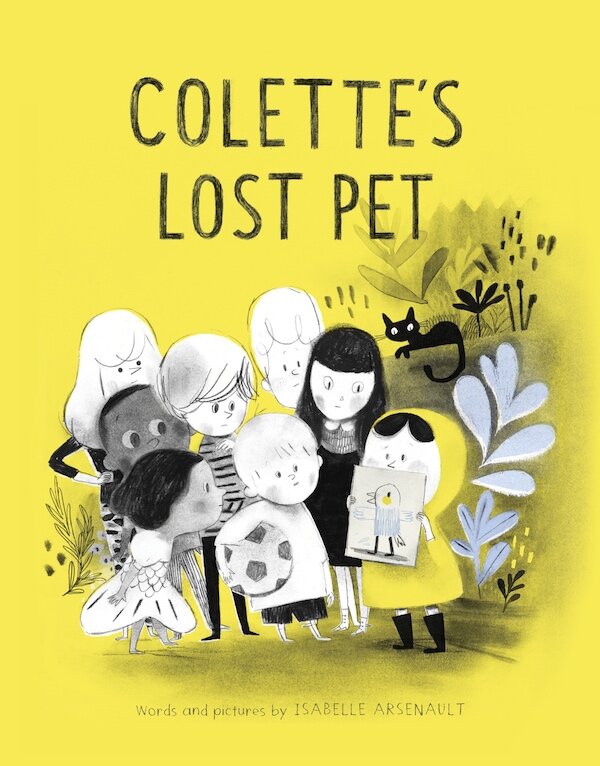

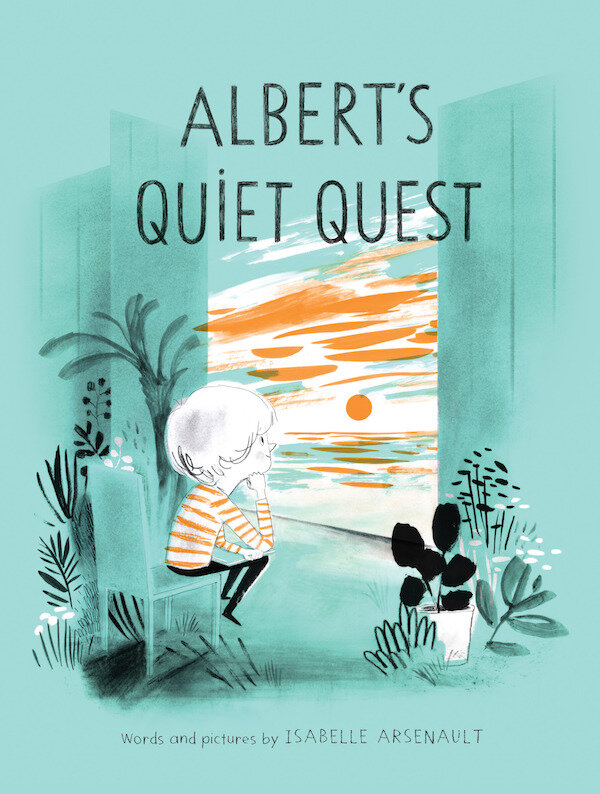

We understand there are two books coming that will complete your Mile End Kids series. Can you explain what the title of the series means? Collette’s Lost Pet and Albert’s Quiet Quest are the first two. Can you give a general preview for the subject of the final two books?

The Mile End Kids series is a collection of books of which I am also the author. The stories were inspired by my own children growing up in an urban environment, more precisely in Montreal’s Mile-End, (but it could be anywhere, in another neighborhood, city or country). I personally grew up in a very natural setting — near the sea — and that’s also where I imagined my children would grow up when the time came. However life had other plans, I settled in Montreal for my studies and I’m still here! At first, it was inconceivable to raise kids in a city with such an obscured horizon, little space and vegetation. But I observed my children playing with friends in the alleys which run behind all the houses, going from one backyard to another, creating imaginary worlds from thin air. It’s this that inspired me to write Mile-End kids. In the books I’ve written, the children’s adventures are sparked from the tiniest detail. A lot of the action happens in their imagination. I play with their perception, their differing points of view, reality and fiction intermingle to create a universe specific to each book in the series depending on the main character in the story. It just goes to show, when we have a fertile imagination, we have access to a world of possibilities that transcend our physical surroundings and the urban dreariness. For the moment, Colette and Albert each have their book, Maya will be next with another to follow. But I hope it won’t be the last! I’d like to write 10 in total, so I’m only getting started.

Cover of Colette’s Lost Pet, Isabelle Arsenault

Interior spread from Collette’s Lost Pet, Isabelle Arsenault

Interior spread from Collette’s Lost Pet, Isabelle Arsenault

Cover of Albert’s Quiet Quest, Isabelle Arsenault

Interior spread from Albert’s Quiet Quest, Isabelle Arsenault

Interior spread from Albert’s Quiet Quest, Isabelle Arsenault

Did you take art classes as a child? Was it a goal early on in your life to become a children’s book illustrator?

I didn’t take any classes outside of those offered in school but I had the luck to have very inspiring art teachers throughout my studies. I was a rather shy child and art for me was a way to express myself and to shine. I often drew, I could spend hours alone in my room drawing or painting. I loved all mediums, trying out and perfecting new techniques. I didn’t really think about where this passion would lead me. It was only at the end of university, when I did a class in children’s books illustration that I considered this as a career. But I started out with editorial and advertising illustration for a few years before finally settling on becoming an illustrator of children’s books when I had my children.

Arsenault’s studio

Do you consider yourself an artist or an illustrator? How do you define the difference?

Illustrators are undoubtedly artists. But I think that when one defines oneself more as an artist than an illustrator it’s because there’s an allusion to the freedom of creation. Despite the inherent constraints in our profession, it’s possible for illustrators to have a great deal of freedom. It’s definitely something I value in my line of work and why it’s important for me to surround myself with people who trust me and support my creative process.

A process and test illustration by Arsenault

What is your approach to illustrating darker emotional scenes for children? Does this process allow you to reflect each project’s unique story?

I adopt an interpretive role whether tackling dark or joyful emotions within a story. I try to convey the emotions through the visual means I have at my disposal: be it through medium, composition, color, rhythm etc. I’ll adapt these elements according to the subject, so as to create a universe, unique to each manuscript. Each project is different and deserves a tailor-made world to go with it. It’s also different when I illustrate a story that I have written myself. In this case, as I have chosen the subject I can guide my graphic approach wherever I choose.

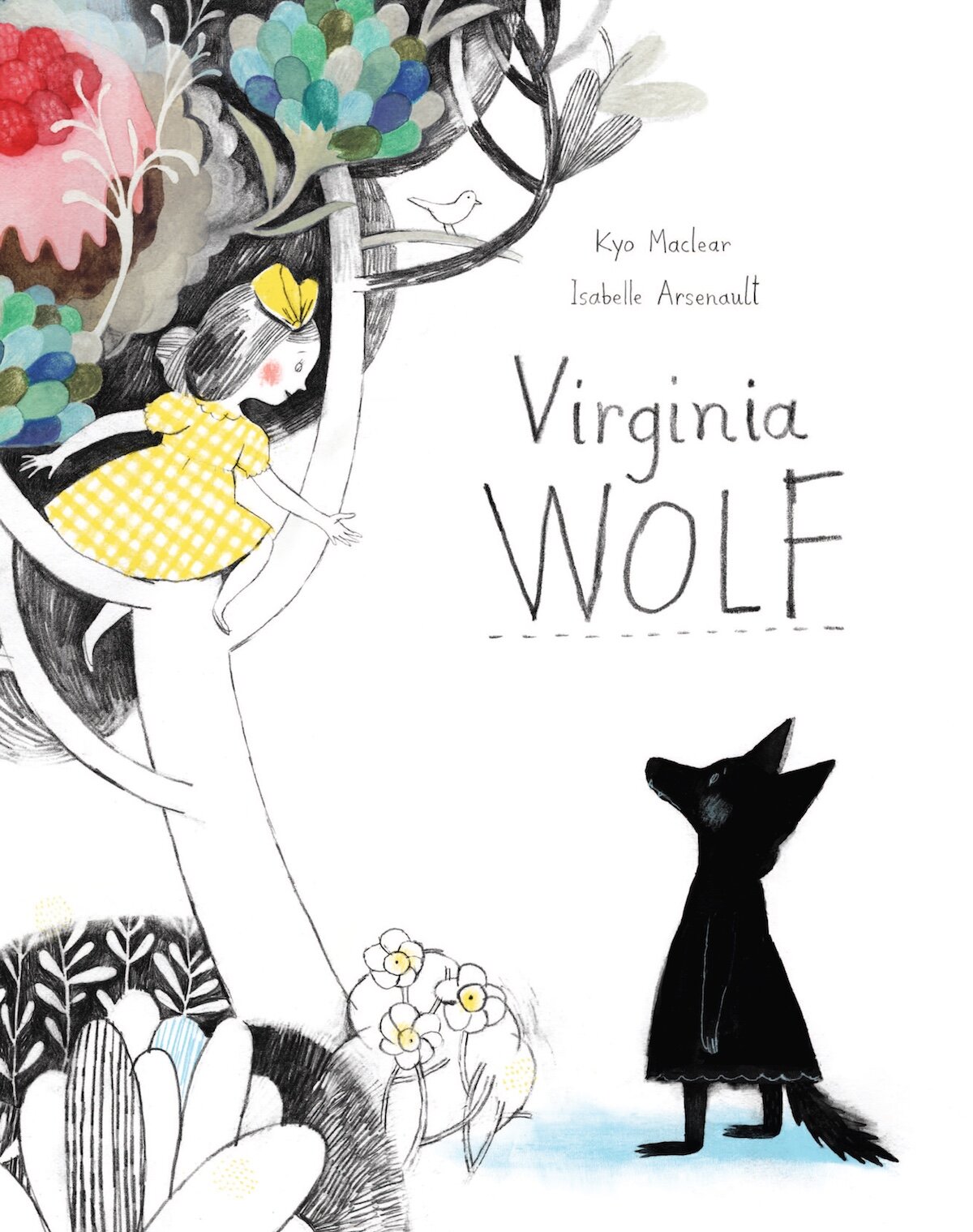

Cover from Virginia Wolf, by Kyo Maclear, illustration by Isabelle Arsenault

Interior spread from Virginia Wolf, by Kyo Maclear, illustration by Isabelle Arsenault

Interior spread from Virginia Wolf, by Kyo Maclear, illustration by Isabelle Arsenault

We admire your selective approach to using color in your work. Can you elaborate on how you make those decisions?

To me, colors are tools that allow me to support the story. Years ago, an illustrator once said to me: colors are emotions. I don’t entirely agree, I think that one can convey many emotions through black and white. But color adds another dimension to the images and in this respect I’m aware of its exceptional impact. Each color carries its own symbolic weight and this is why I like to limit my use of color to the one that most supports the subject.

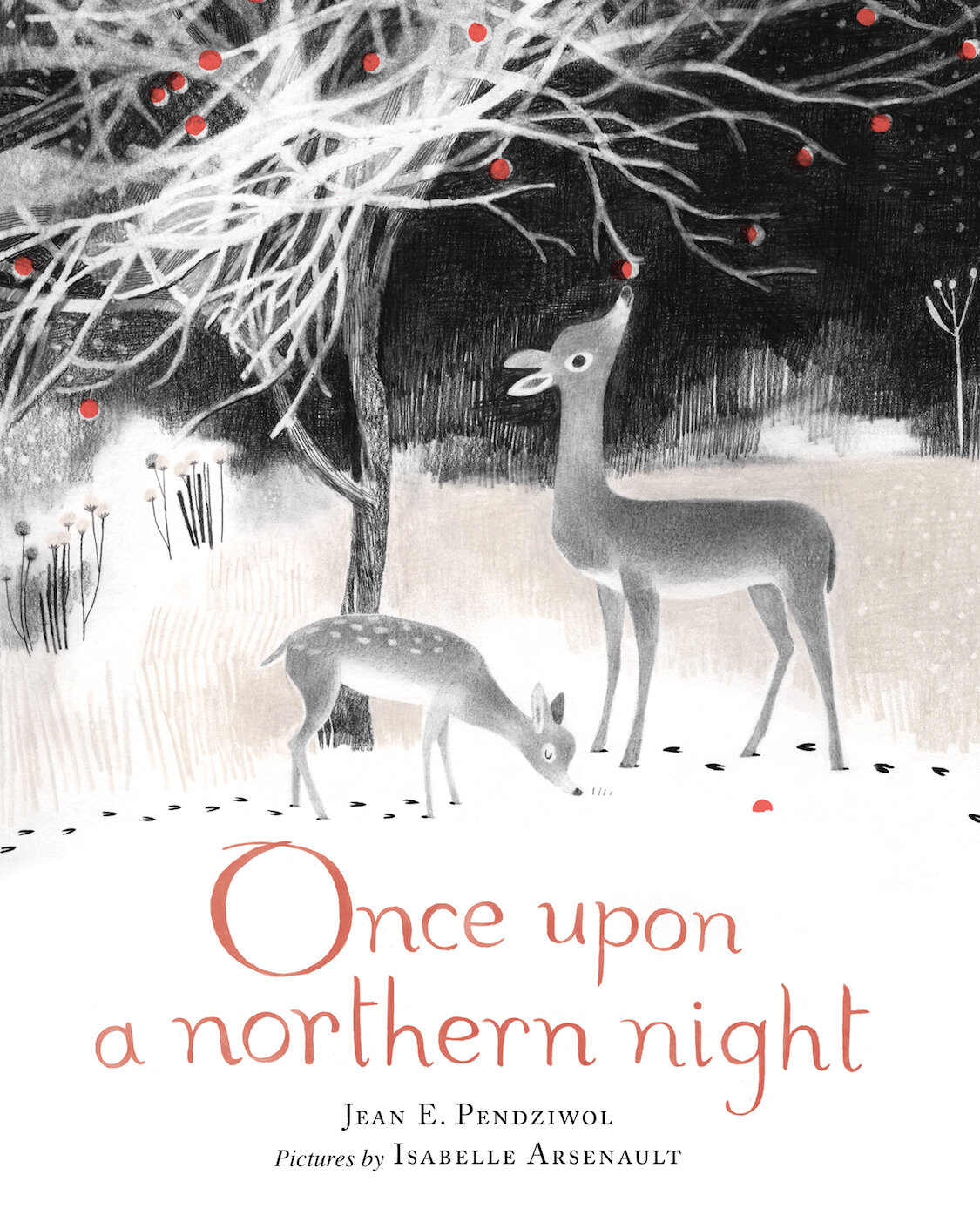

Interior spread from Once Upon a Northern Night, by Jean E. Pendziwol, Isabelle Arsenault

Cover from Honeybee, by Kirsten Hall, illustration by Isabelle Arsenault

Do you keep an on-going sketchbook? If so, how does it inform your work?

I’m a little wayward when it comes to keeping a sketchbook. I always have one to hand but I’m not systematic in putting pencil to paper. This year, I said I would do a sketch a day based on something in the news that day. I was disciplined for the first 100 days of the year, but then I lost interest. Maybe the news depressed me a bit as well … Nevertheless I did appreciate having a structure, a concept that provided a consistent routine.

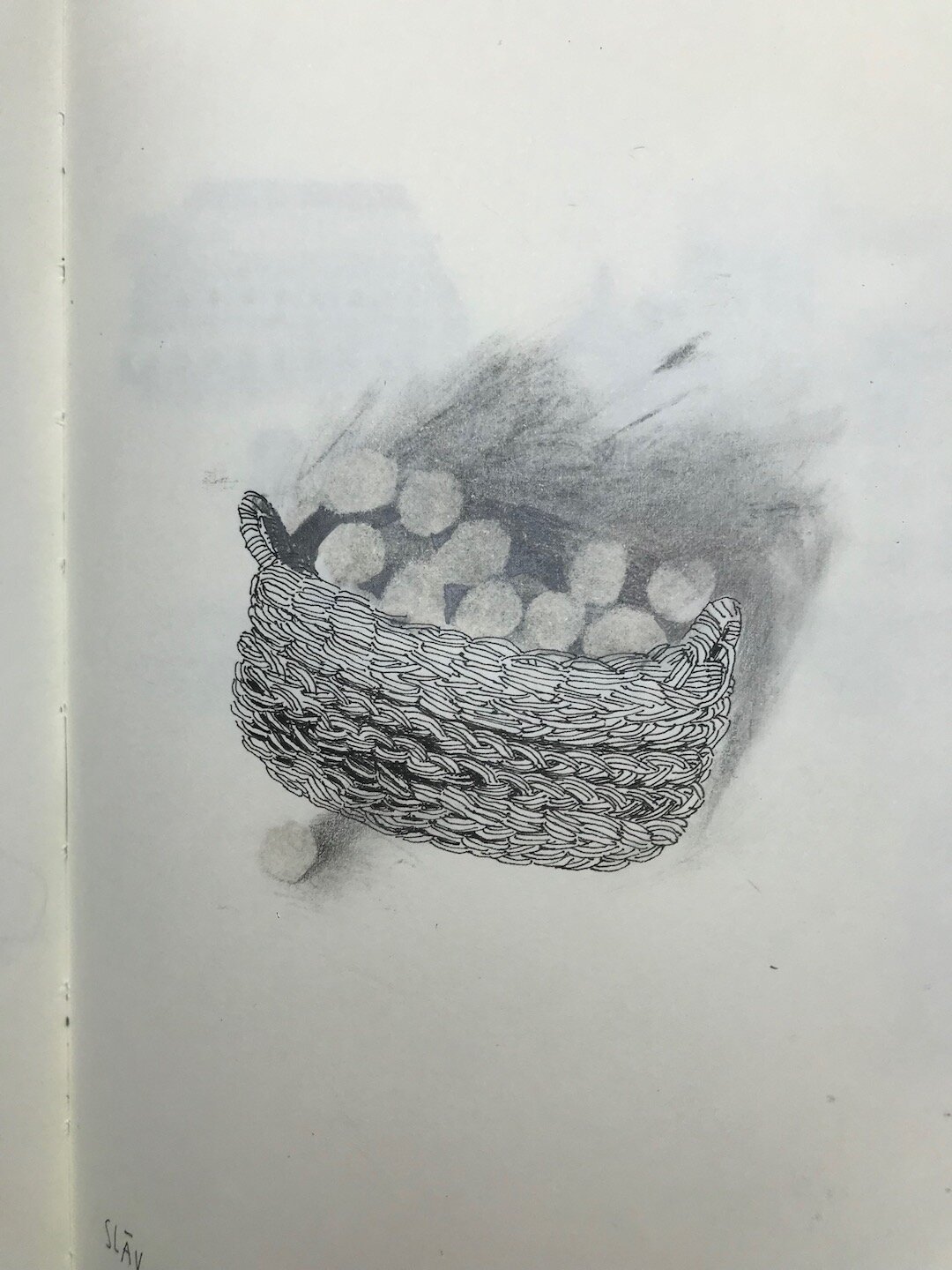

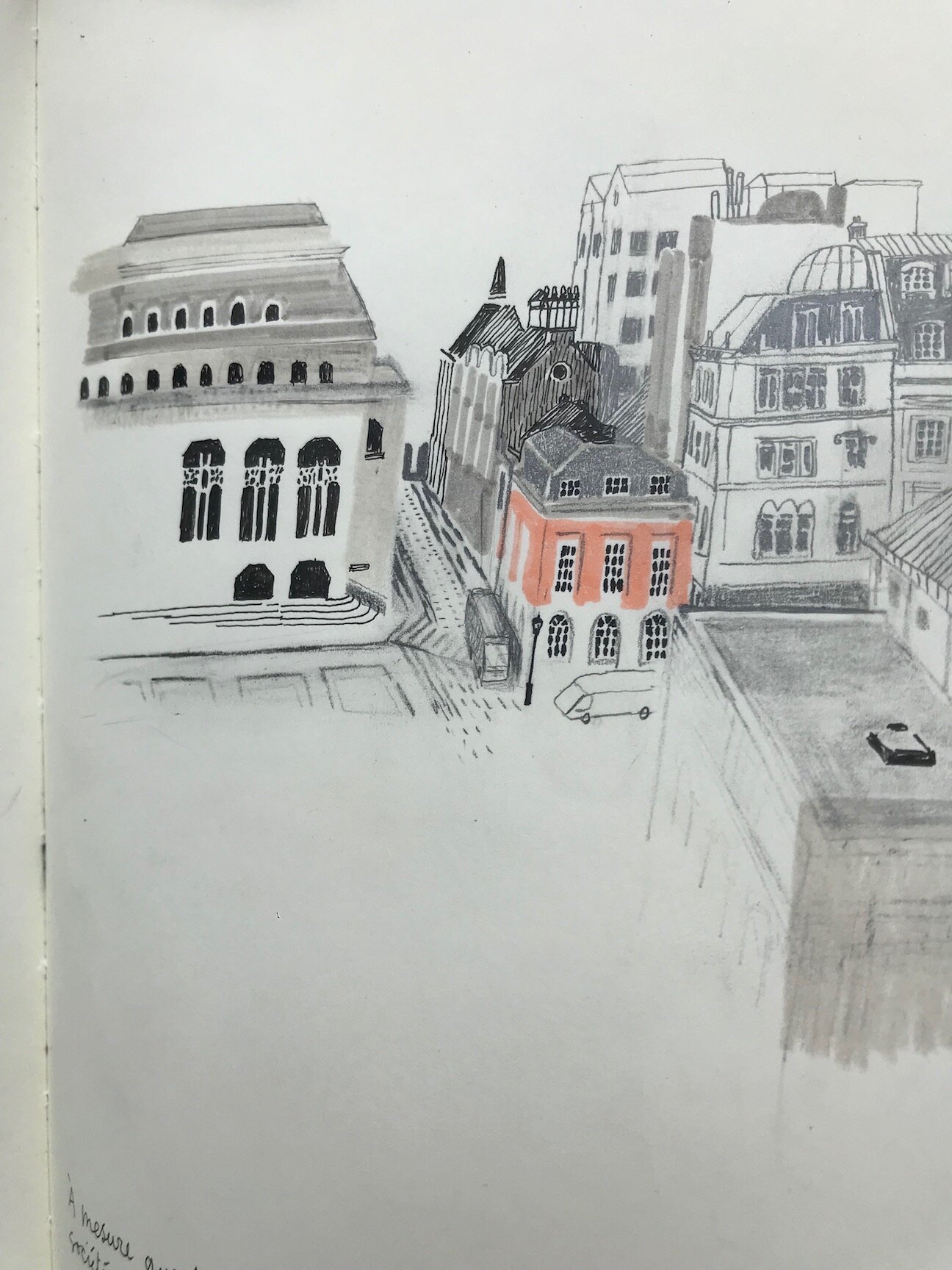

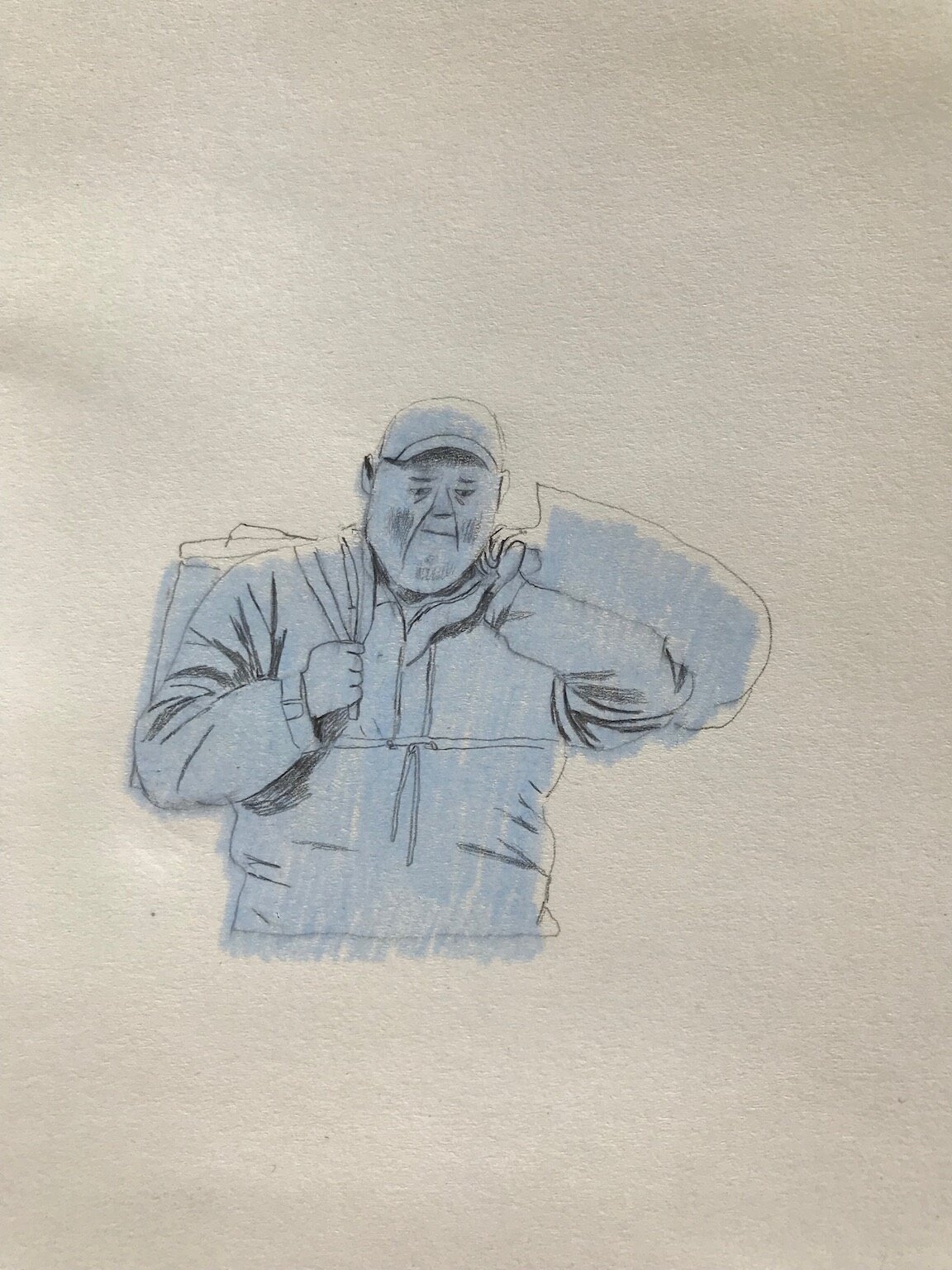

Images from Arsenault’s sketchbook

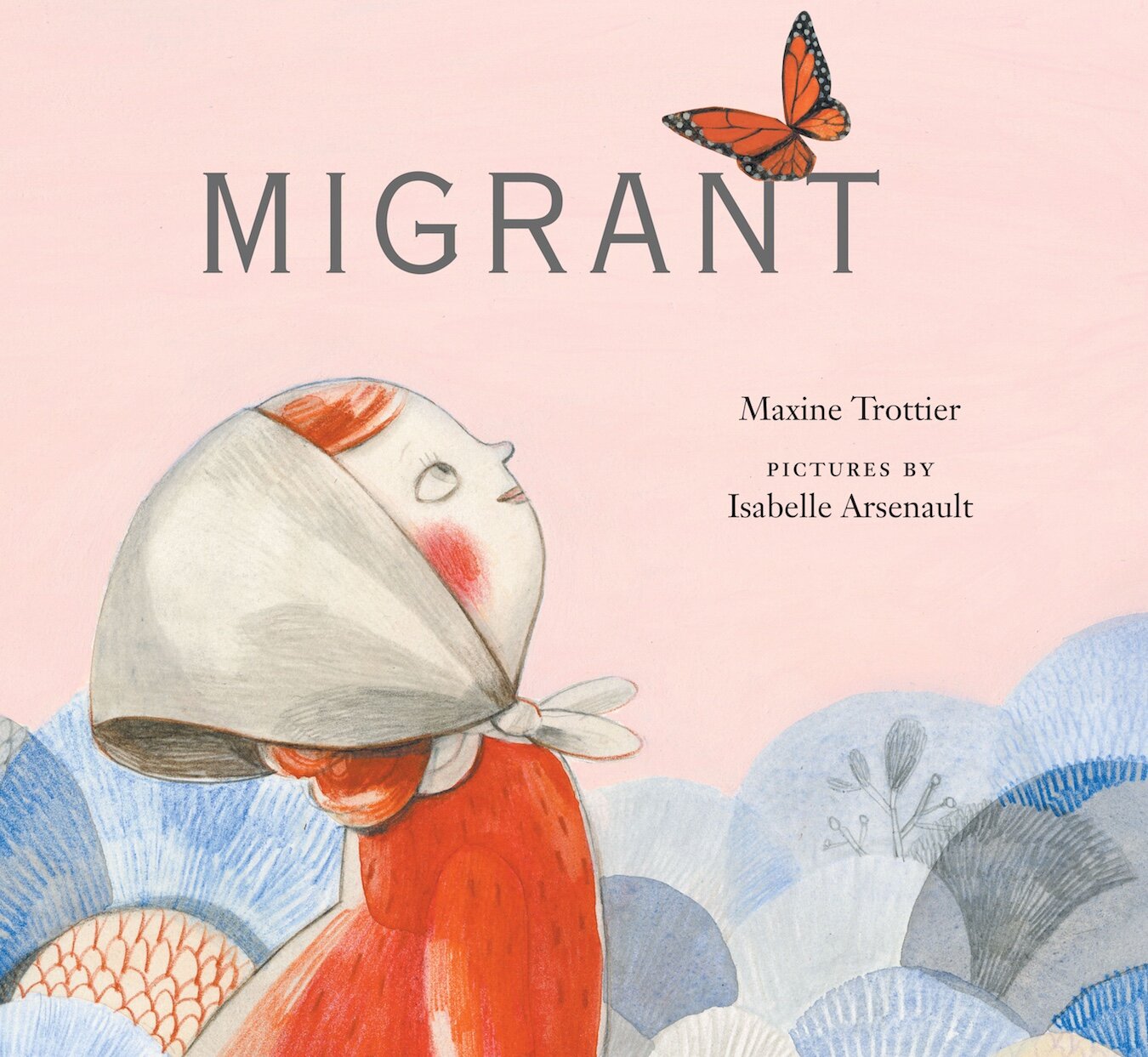

Migrant, by Maxine Trottier, (published in 2011), is a storyline that continues to be sadly contemporary. Your illustrations are beautifully impactful. How did you go about developing your art style for this book?

That book came out a number of years ago now. I was learning about illustrating books on the job! For this one, I was inspired by the patterns on the quilts which, for me, were representative of the traditional aspect of Mennonite culture. In my research, I learnt that a common pattern in quilting was called “flying geese” which I found symbolic given that the text compared the seasonal migration of families for agricultural purposes, to wild geese. I integrated this pattern composed of triangles into my illustrations, using elements of collage, that for me also made reference to a change of life, a transformation, to their reconstructed, patchwork lives.

Cover from Migrant, by Maxine Trottier, illustration by Isabelle Arsenault

Interior spread from Migrant, by Maxine Trottier, illustration by Isabelle Arsenault

Interior spread from Migrant, by Maxine Trottier, illustration by Isabelle Arsenault

Interior spread from Migrant, by Maxine Trottier, illustration by Isabelle Arsenault

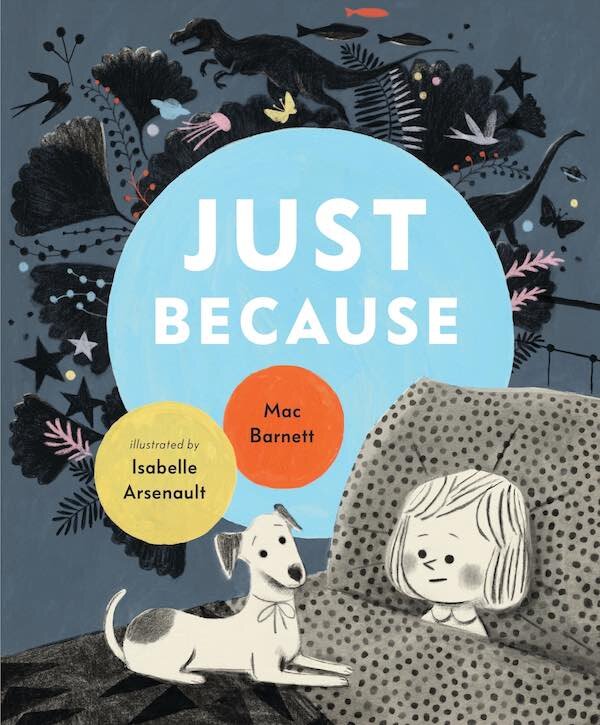

Your two recent books are by other authors, Captain Rosalie by Timothée de Fombelle and Just Because by Mac Barnett. With Captain Rosalie, were there special challenges you faced in illustrating a longer format story?

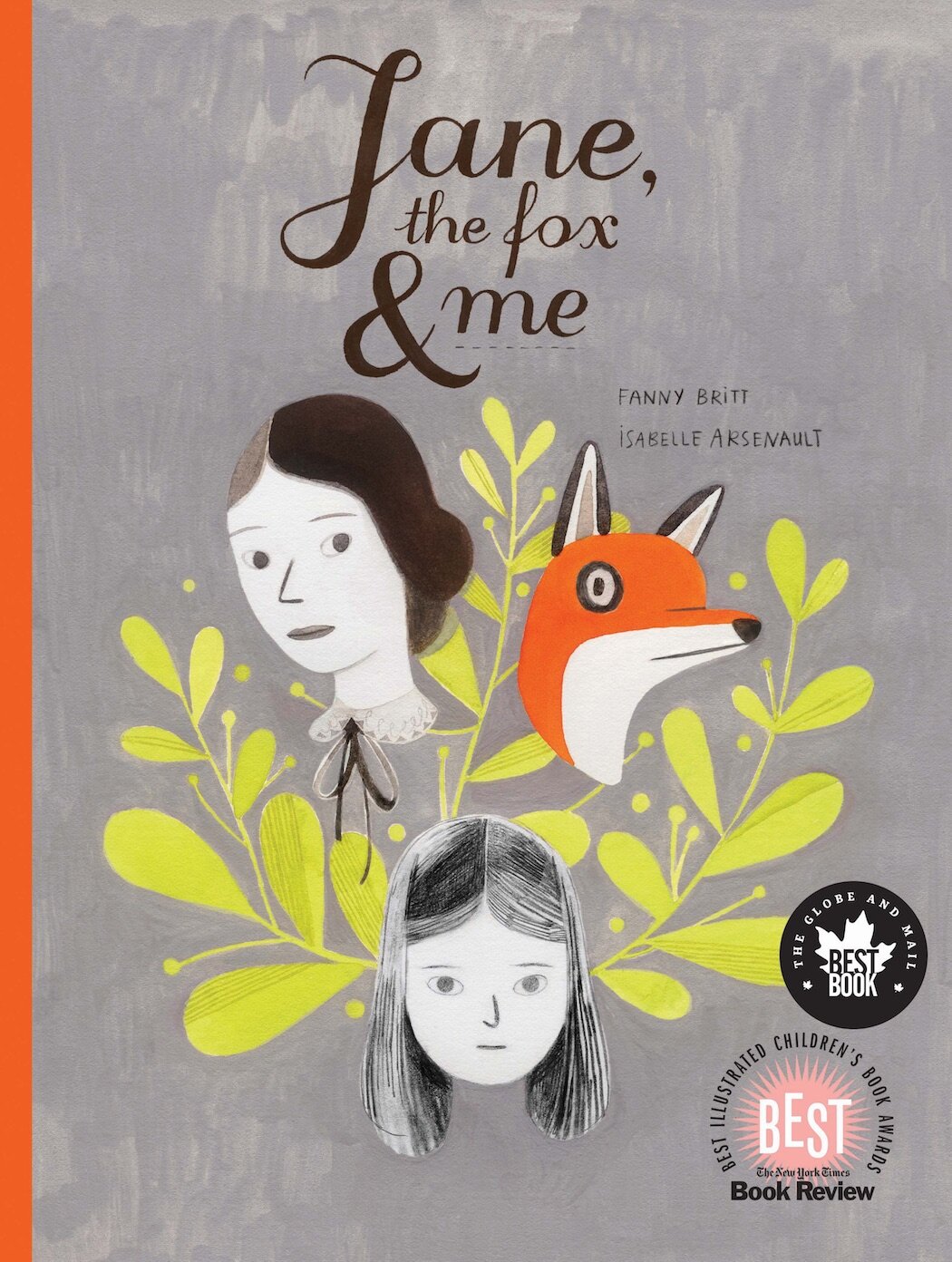

Captain Rosalie, even though the text was longer, didn’t necessitate more work for me. it was the first time I have illustrated a chapter book and I very much enjoyed the experience. The illustrations in this book are more narrative and there aren’t many so that took off a bit of the pressure seeing as the book relies less on visuals than on text. I found the project refreshing and it makes me want to repeat this kind of collaboration. As for special challenges faced in illustrating a longer format story, I would have more to say on my graphic novels: Jane, the fox & me and Louis Undercover (Fanny Britt): both of which are over 100 pages and fully illustrated. In this case, the challenge is mainly finding time to concentrate on these long-term projects while still remaining in contact with the rest of the world.

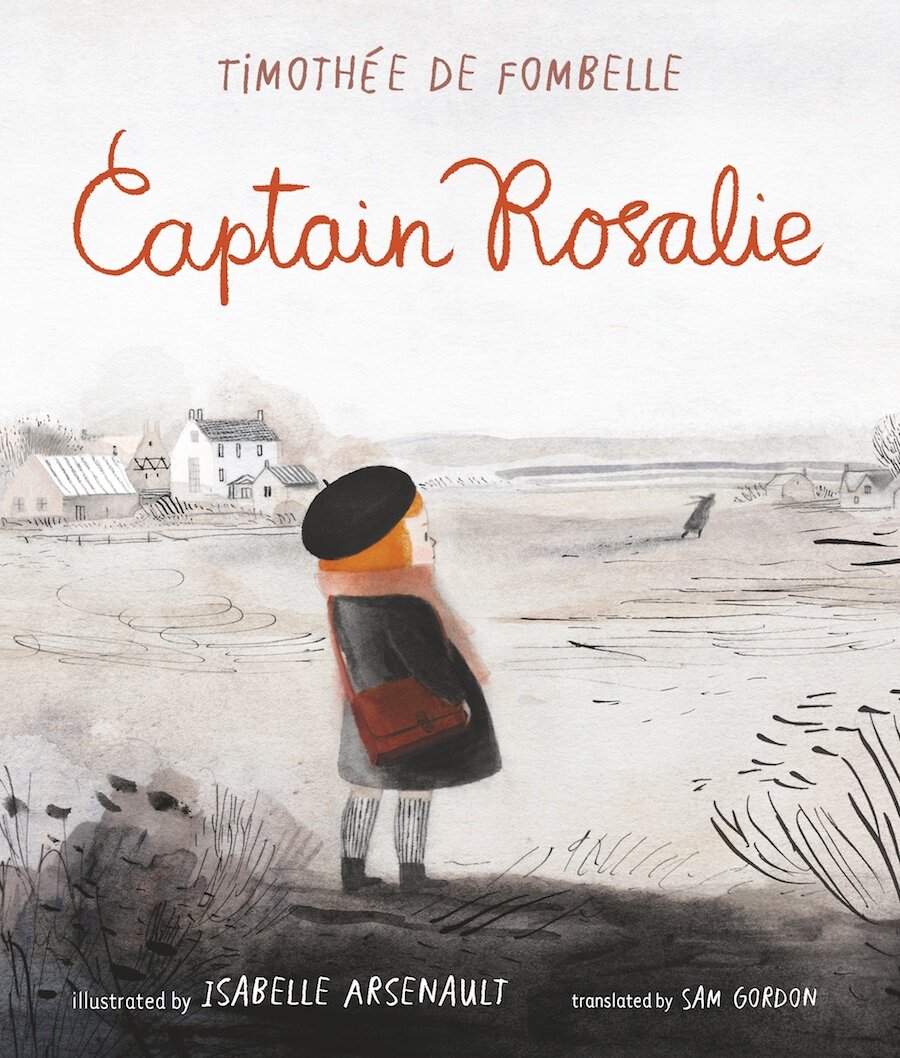

Cover from Captain Rosalie, by Timothée de Fombelle, illustration by Isabelle Arsenault

Interior spread from Captain Rosalie, by Timothée de Fombelle, illustration by Isabelle Arsenault

Cover from Just Because, by Mac Barnett, illustration by Isabelle Arsenault

Interior spread from Just Because, by Mac Barnett, illustration by Isabelle Arsenault

Cover from Jane, the fox & me, by Fanny Britt, illustration by Isabelle Arsenault

Interior spread from Jane, the fox & me, by Fanny Britt, illustration by Isabelle Arsenault

Interior spread from Jane, the fox & me, by Fanny Britt, illustration by Isabelle Arsenault

What was the most useful advice you received as a young artist? What would you say to an artist/illustrator starting out in the field today?

One of my university teachers in illustration (Pol Turgeon) said that illustration can touch people by the strength of its beauty. However the impact can be multiplied if the illustration also manages to communicate an idea. In reaching out not only to the eyes, but the brain. I always keep this in mind. As for my advice to anyone starting out, something else I also find very important, and I’ve learned this over the years, is not to neglect the notion of pleasure. It’s an excellent guide in this line of work. Those moments when I‘m really enjoying what I’m doing, deriving joy from my work, where everything else disappears, then I know I’m heading in the right direction or that I’ve attained my goal. It’s an unmistakable sign. Following your instinct is essential in order to make good decisions, like choosing one text over another and remaining true to yourself. You can tell right away what works and what doesn’t if you’re attuned to what you’re feeling inside. When a creation is tainted with frustration, discouragement or a sense of failure, it’s often because we’re aiming for a result that’s too precise, that holds too many expectations or external considerations that aren’t our own. When we free ourselves from these preconceived notions and we develop our own language, then we can start producing our best possible work.

Thank you, Isabelle, for sharing your work and creative process.

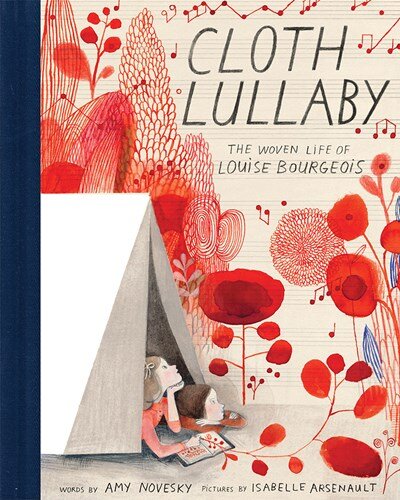

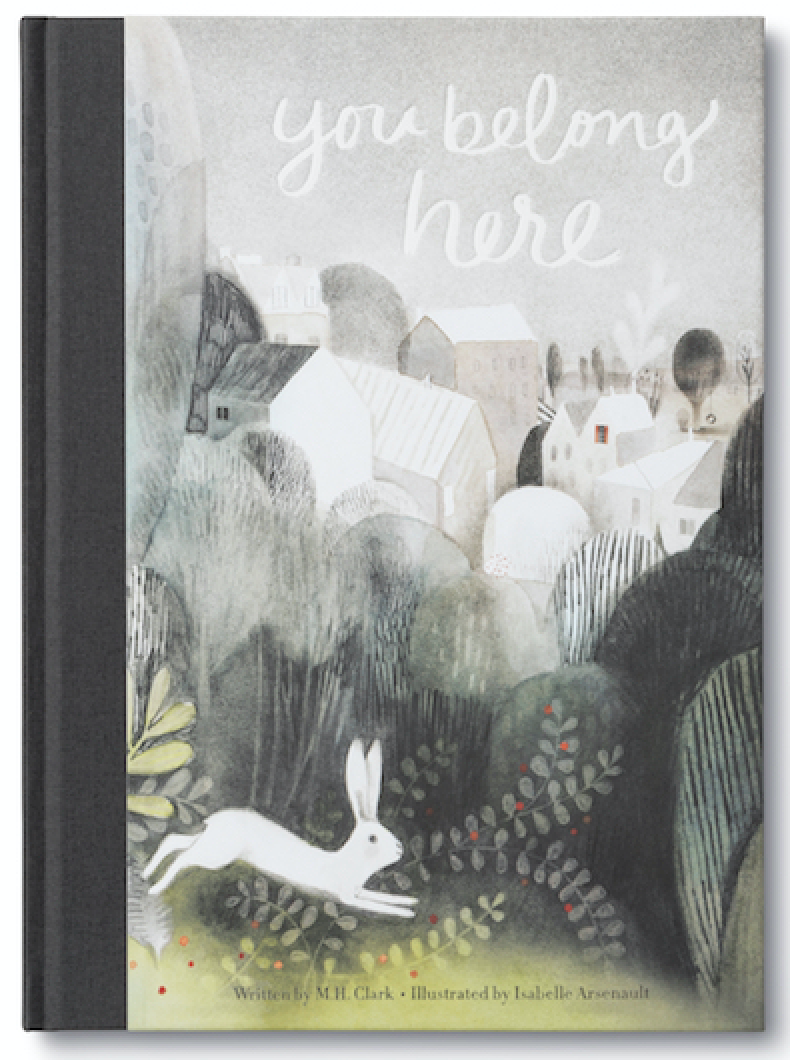

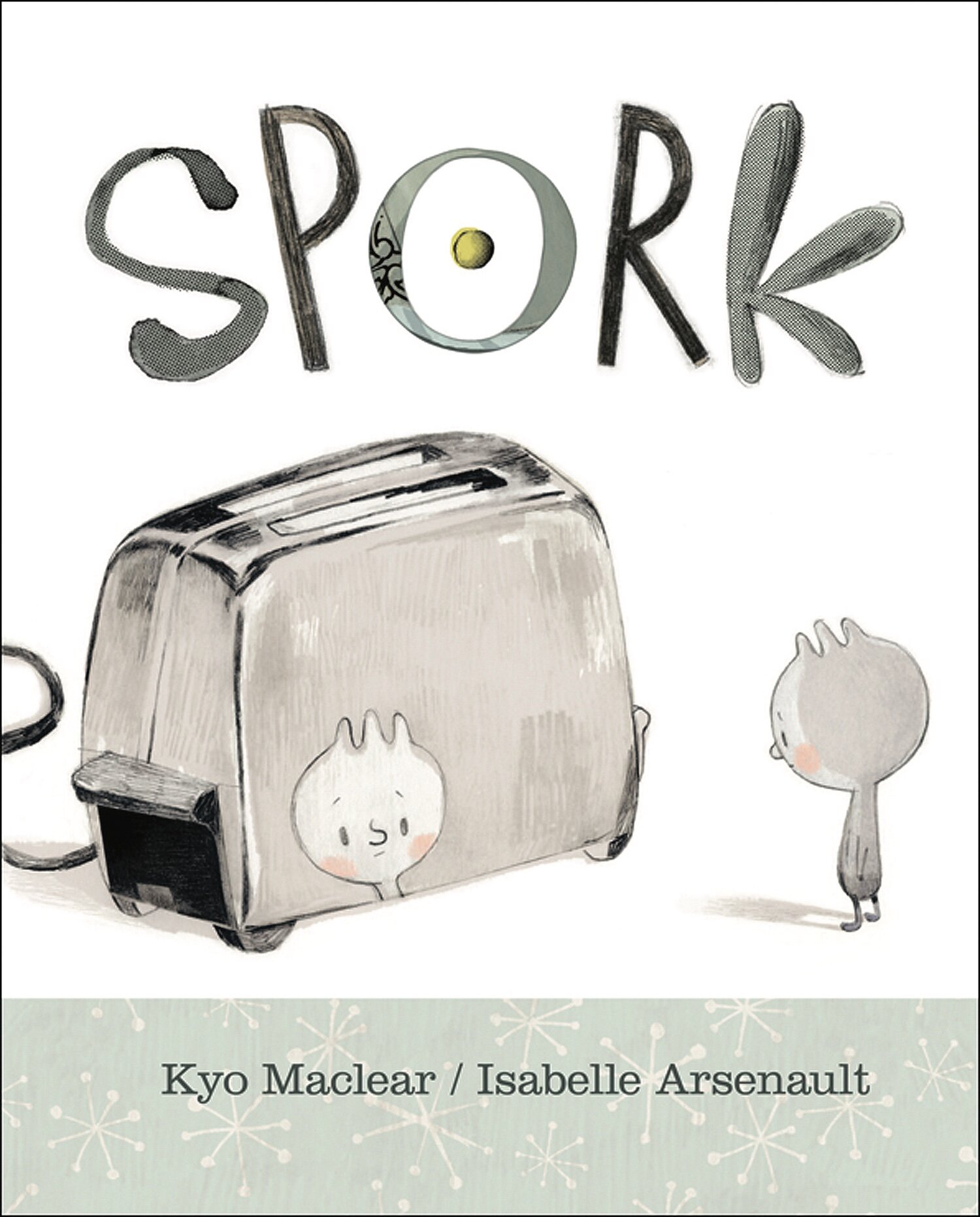

A selection of Arsenault’s work

For more on Isabelle Arsenault:

An interview with Isabelle Arsenault and Mac Barnett

All images used with permission by Isabelle Arsenault and the publishers listed below.

Captain Rosalie Text © 2014 by Timothée de Fombelle. English translation © 2014, 2018 by Walker Books Ltd. Illustrations © 2018 by Isabelle Arsenault. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA on behalf of Walker Books, London.

ALPHA © 2014 by Les editions de la Pasteque. Concept and illustrations © 2014 by Isabelle Arsenault. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA.

Migrant © 2011 by Maxine Trottier, illustrations © 2011 by Isabelle Arsenault. Reproduced with permission of Groundwood Books Limited.

Jane, the Fox and Me © 2012 written by Fanny Britt, illustrations © 2012 by Isabelle Arsenault, English translation © 2013 by Christelle Morelli and Susan Ouriou. Reproduced with permission of Groundwood Books Limited.

Once Upon a Northern Night © 2013 written by Jean E. Pendziwol, illustrations © 2013 by Isabelle Arsenault. Reproduced with permission of Groundwood Books Limited.