An Interview with Jon Klassen: A Return Visit

Jon Klassen

February 24, 2021

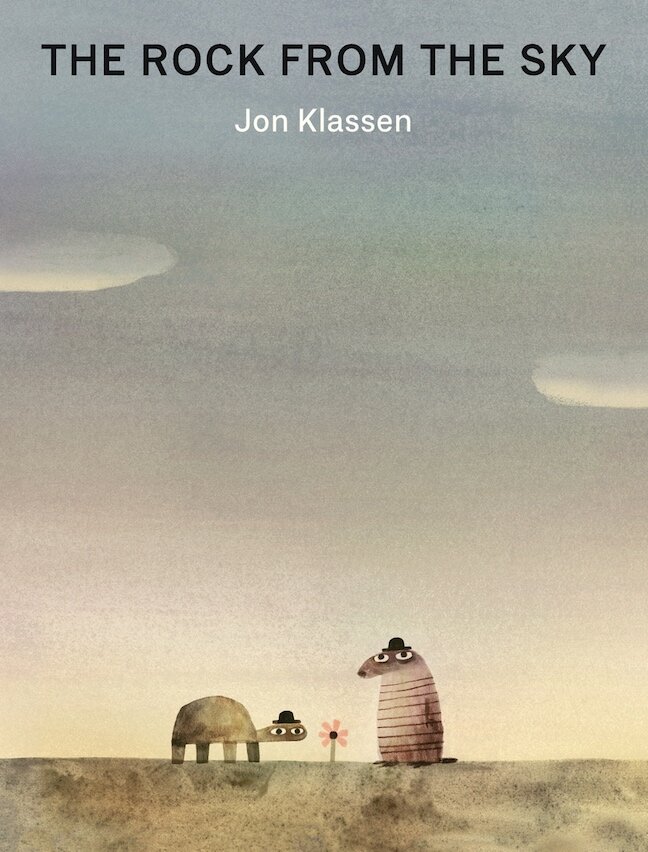

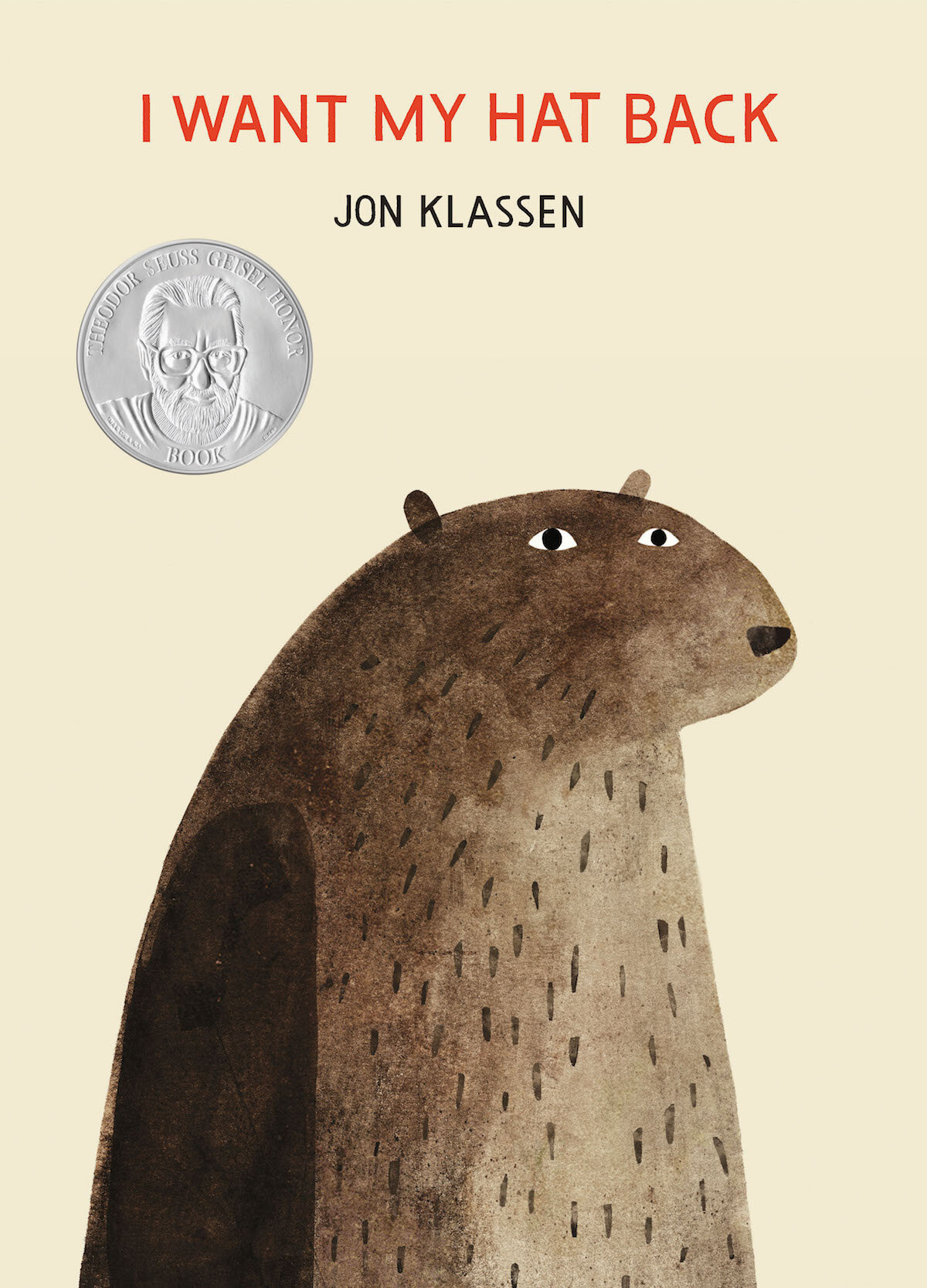

We interviewed Jon Klassen, award-winning children’s author and illustrator. In this return visit, he discussed his latest book, The Rock from the Sky, and the creativity and process involved in writing and creating art for picture books. He lives and works in Los Angeles.

A Selection of Work

Cover of The Rock from the Sky, Jon Klassen

With The Rock from the Sky, a book of five related stories, do you feel you got any closer to the immersive stories you liked as a kid?

Hmm, that's a good question. I guess that was a goal, or a sideways goal, to see if it could feel like we lived there for a while. I'm always going back to a structure that feels like you did a day, or a year, or around the clock where it starts in the morning and ends at night. That was definitely a peripheral goal; to feel like you've spent time with these characters and in that place, but I'm just sort of guessing if that's going to work. I'll always hope for it but immersion is not something I would know how to engineer for sure. I'm always surprised that it happens. It's almost a click of, "Oh, I'm in it. It's happened." It's a really magical skill, as close as a storyteller can get to being a musician, when you just do this magic thing. It's something I've admired about people I've worked with, film directors and other authors or illustrators, who just seem to know how to do it. I'm not even sure they know they're doing it, but it's like, "Oh, there, they did it again. It's breathing."

So it's tough to analyze that, separate it out and say this is the formula.

Yes. The time of day device is an attempt at that, though. As a side road to that point, we've been watching "Looney Tunes" cartoons with my son, who's almost four. I used to watch them too, we had a VHS tape that was a collection of the popular ones. The last half hour of the tape was just solid Roadrunner and Coyote, and the very last cartoon was set at night. They never did a Wile E. Coyote one at night! It was always in a middle-of-the-day, flat desert. But here was one episode where he was on a rocket he'd built that was blasting him up into the night sky and exploding into stars and that was the end. It was usually dark out for me watching it by then too (we lived in Canada) and you really felt like you'd had a day in this movie and this was the end. It had that melancholy feeling and sadness of the ending, that it was over but also that it was rich, that you had hung out there for that long, that the sun had gone down. It's such a simple device: to go into night-time at the end of the day. I like the simplicity of that. Kids are often read to before bed so it's natural for it to be night at the end of a book, when everyone goes to sleep. It is such a great way of making you feel like the whole thing is settled down into this world you've made.

Do you ever make any changes after the "uncorrected proof" before its final publishing?

It's mostly visual changes. My illustrations tend to run cold when they're printed so we generally try to warm them up overall. We have a go-to formula in production about how to bring that around by now. With this book, it was tricky because the sunset and night-time stories were sensitive to print because they are so dark—I knew going in we were going to tackle that at the end. But with writing or changing any of the pacing, that doesn't happen at the proofing stage anymore. I almost make a rule of that. With proofs, when it's your own writing, you could theoretically change anything, at any stage, because it's all yours. Picture books are susceptible to that because they're so short, you're making such big moves on every spread, you can make huge changes so fast. But at a certain point you have to shut your brain off and understand you're locking it.

Interior spread from We Found a Hat, Jon Klassen

What about the research you did for illustrating this book—for the skies, for instance?

The skies were really tricky, for me anyway. This was the first book, at least of my own, where I've attempted any full bleed backgrounds (though the third Hat one, We Found a Hat, had some plants). But as far as convincing readers of something in the background, like a sky, I'd never done that before, or at least never with the intention of fitting it in with the rest of my own "book world." This one just felt like it needed it. There was a rock up there somewhere and you want to feel the expanse of it. I just didn't think it was going to feel as good without a sky. I didn't want much of a sky, just some variation and lighting changes. I called some illustrators I know who are really good painters to ask "How do I get this?" My friend, Chris Appelhans, who always knows what to do with paint, and Sydney Smith who is just, you know, Sydney. Amazing painters. But I didn't want anything too difficult, I didn't think. Just a quiet wash. I was getting close to what I wanted, but not exactly. Every time I tried, it just distracted from what the characters were doing, it was too busy. I ended up with five or six washes that I played with afterwards. I think the whole book is made up of about ten washes. Then there are three or four digital stages to it, which are just as important as whatever you do on paper initially. I just really wanted something very soft. One of my first jobs, as an intern, was at the Shaw Theater in Ontario. They would paint backgrounds on these big drop cloths, the size of a house. They would spend all day nailing it to the floor and then take brooms and wash it with huge buckets of paint to make big, soft skies. It was such a cool process, to watch people walk across this warehouse floor painting a giant sky. Standing with them on the ground, it looked like someone washing a floor but when you pinned it up and lit it, it looked beautiful, like a great, soft sky. That's what I wanted. This book is supposed to feel like it's happening on a stage. But I didn't want to call it out literally, with footlights or strings coming down from the clouds. I wanted it to feel theatrical but only in the way of broad strokes, the general idea.

Interior spread from The Rock from the Sky, Jon Klassen

Can you describe how you combine watercolor with Photoshop?

The painting stage is mostly about noise. It's not even about the value yet because you can punch that up digitally. From what I know about photography, I liken it to the same process as taking a photo on film, then bringing it into a dark room and finding out what the photograph actually is. How you deal with the exposure makes the photograph. Taking the photograph has all these unpredictable things happening in front of you, which is how I feel about painting too, but then when the image is taken and set, when you get to bring it in and fool with it, that's your language. That's what you're bringing to the photograph. So much is in the development. That's how I want to view these images too. I want a certain kind of noise, but I don't have anything specific in my head until I see it. Often if you play with it too much it and then it looks burnt or over processed or something breaks it. Part of the trick is to find a sample or a wash that wears a lot of manipulation well, that you can't tell that it's been played with too much, hopefully. I go back and forth on this a lot, the ethics of it, I guess. I think ethics is the right word for it, whether I should try to get them to look naturalistic through a digital process, or should I just learn how to actually paint. I just want the image that I want for the book. I don't ever feel bummed out that there isn't an original somewhere. But so much of my impulse is to make sure it doesn't look digitally manipulated, so what is that all about? It's a conversation that I think I haven't really had with myself yet.

You have used the phrase "fooling yourself into doing it" for making picture books that seems on point for many creative pursuits: art, writing, etc. Can you describe the "negative space" around your hang-ups or anxieties and how that informs your work?

I think the specific hang-ups and anxieties probably change. My hang-ups and things I'm nervous about are different than they were when I was doing my first books, especially when it comes to the writing. I think I've started to come to terms with being the writer I am vs. the writer I thought I wanted to be. I love reading description and I like people who can write description. My favorite children's writers write nothing like I do; they're naturalistic. And it comes out in a way that doesn't seem calculated or stiff or nervous. But I write best that way. It's the only way I can write, actually. I was trying to be more flexible with the Hat book series, at least as far as what the stories were about and how they felt, trying to be less stiff. They get a little bit sweeter, a bit more emotionally present, and less sarcastic as the series progresses. With this one, though, I've reverted all the way back, it feels like! Every time I had an impulse in the writing, it was to see how far I could stretch the stiff feeling, the feeling of it being really stagey and deliberate. We're going to spend eight spreads looking at a sun going down. Nobody moves in this story, etc. On the other hand, I don't want to seem like I'm making fun of the form or being sarcastic or cynical about it. Children's books are so deliberate and so short and all their pages have to really count—it's a highly pressurized format. The idea of calling that out and then rebelling against it and having the sun take that many spreads to go down really appealed to me. It felt like I could do that without being cynical. I was hoping children would be with me on that and think "This is exciting because it shouldn't take that long in a book like this." Another part of fooling myself into doing it is to set weird goals in the story to build around. With this book, in the first story especially, what I really wanted was just this spread of a rock by itself, just hanging over nothing, just floating. In every book, I try for a spread that, on its own, wouldn't make any sense without the surrounding story. You wouldn't even know if it's falling if you weren't told by the previous images, or the title. And we actually had to add these little pebbles above the rock, to show its motion. I didn't want to do that but I could see the reasoning. But on the back cover, I won that one because there are no pebbles. I just liked the idea so much: that it could be floating, if we didn't know. It ends up as a surreal image that is inexplicable unless you read the story.

Interior spread from The Rock from the Sky, Jon Klassen

Speaking of those characters that are beneath that rock, how do you relate to your characters? Do they reflect you a bit?

I think they all do, in different moments and in different relationships. I think when I write about the turtle, I'm thinking about the relationships where that's who I am in it. When I think about the other guy, the mole-thing, I'm also that person in different relationships, with different dynamics. Then there is the snake, and whatever he is supposed to bring to the story, but I'm him too. The snake came out of necessity a little bit. I had these two guys under this falling rock, but I couldn't get the turtle to move. Why would he move? He wouldn't want to. The story starts with the turtle saying he would never want to move. I had a few ways: would he go over there just to hear the other guy? He wouldn't do that. He's not that nice. But then the snake walked out and started this other relationship, and then the turtle starts to move, and that was a surprise, to me. I was like, “Oh, he's jealous!” Of course, he doesn't want to say he's jealous, but it endeared him to me, and it got him out of there. I think the book came about because these two characters, the turtle and the mole-thing, don't know how to say that they like each other. The mole would come to it easier but he's too nervous, he doesn't want to risk breaking what's there, so he won't say it. And the turtle is too proud, he doesn't want to say it. He might not even know it, until it’s threatened. So neither of them ever actually lay it down, that they enjoy hanging out with each other. And they don't even by the end of the book. It almost comes to a breaking point but circumstances at the end kind of trap them together. Which is what you hope for when there's someone who you're with where you haven't done a great job in expressing how you feel—maybe the world will just trap us together. I don't think the turtle is going to make any big moves for a while after the book ends. The turtle is easy to write because I find that my strongest stuff is when I access the jerk, who can be un-filtered and mean to the other characters. I'm not like that, really, so it's fun to just let it out. But it's transparent too, he's not fooling anyone.

You're describing the micro-dramas from so many people's childhoods! Do you think that's part of the reason kids respond to your books?

I hope so! That's what I found in books when I was little. Recently, I was talking about Frog and Toad and why it was just so strong when I read it. A large part of that was reading about those two characters and seeing this unresolved, uneven relationship, where one of them needed one of them more than the other. Even in third grade, a kid has stuff like this. You're thinking: I know I have friends who would easily leave me and I have other friends I would leave. I don't like them as much as they like me, and vice versa. You're in second or third grade and you're recognizing those dynamics happening. I don't think it's very interesting to describe those relationships to kids in an analytic way. But it is really interesting for them to just watch that play out and validate that they exist.

When you do pre-K or elementary school events, what are kids curious about? Do you see a change from kids' questions or reactions to your work from years ago?

No, I think mostly the kids still react to the larger stuff in the books that you hope is going to hook them. Like: Was the rabbit eaten in the first book? They want to know the bigger hooks you put in on purpose so you do have something to talk about. I wouldn't know how to answer the subtler questions, if they had them. That happens more with parents. They want answers. "Why would he do that?!" I don't know why. I don't know why anyone does anything! I wouldn't know what to tell them as far as motivation. But that is what the books are about: people doing kind of inexplicable things to each other. You understand why in an unexamined way: You get that that character would do that, but you wouldn't know how to explain it. So yeah, the parents' questions haven't changed much. For the kids, oddly, the questions have become a little more about me. As I get older, doing this, the books have been around for longer, and maybe they've had more of a presence in their lives. So they want to know who made them. That didn't happen before. It was more: What's this book about? But now it's: Who are you? And that's weird because it doesn't seem that long ago to me that I started making them, but I meet siblings who are older and they say: I had that book when I was little!

Do you have a favorite spread from your new book?

I'm almost proud that this one doesn't have a spread that stands out, because they all lean on each other. But I was pretty proud of the alien spread, when he first walks out. He came out of nowhere, late in the game, as far as the writing goes. I had all these stories set up without him. I always have to push myself to put something dramatic in because my usual gear is always so low, but it's almost like I have no idea how to go, only sort of go big. It's either a story about taking a nap, or a life or death one. Is it too quiet? Let's bring out a Death Alien. That'll do it.

Interior spread from The Rock from the Sky, Jon Klassen

The last spread of the whole book, with just the two rocks and no text, might be a runner-up for favorite spread. With that spread, if you hadn't read the book, you would have no idea what's going on in that picture. With the alien spread, there is something interesting happening objectively. But the last spread, with the two characters standing wide-eyed between two rocks, your audience is doing all the work there for you. You've built everything behind that image and by now you know why the rocks are there, and what's under them, but on its own it's a very calm image, nothing is moving. Maybe that's a better answer for favorite spread. That one has the whole book behind it, built into it.

Is there a page or spread that is totally different from your initial concept?

The alien—at all! I didn't know about him when I started writing that story, even. I think I got four or five spreads into it and him showing up was as much a surprise to me initially as to the characters. It has so much to do with what the book is about for me. Just feeling completely out of control in terms of where everything is going around you. The book is largely about living with what you can't control, but looking into the future is especially sort of futile. You can get partway there. It stands to reason that trees would get bigger, but there is also the unknown. The alien is the unknown. You don't even know if he's an alien. I don't know what he is. We're not supposed to know. And I like that too, to say to kids that we don't know. It's starting to happen here with our kids at home, where they ask a question and I'm like: Gosh, I don't know! With the mole being the savant, the future predictor, at least in the first story, he doesn't know either. He doesn't try to explain it. The turtle is asking him all these questions and he usually has something as an answer, but the alien comes in and the mole says: I don't know. As soon as the alien did come out, I thought, well, he has to come back for the end of the book too. He's in the world now and we have to deal with that. But for that whole story, I didn't know the alien was going to show up.

Interior spread from The Rock from the Sky, Jon Klassen

It seemed to work out well.

I hope so. Even if the kids don't go for my whole Samuel Beckett nod in the first few stories, when a one-eyed alien appears, maybe I'll hook a few kids with that one.

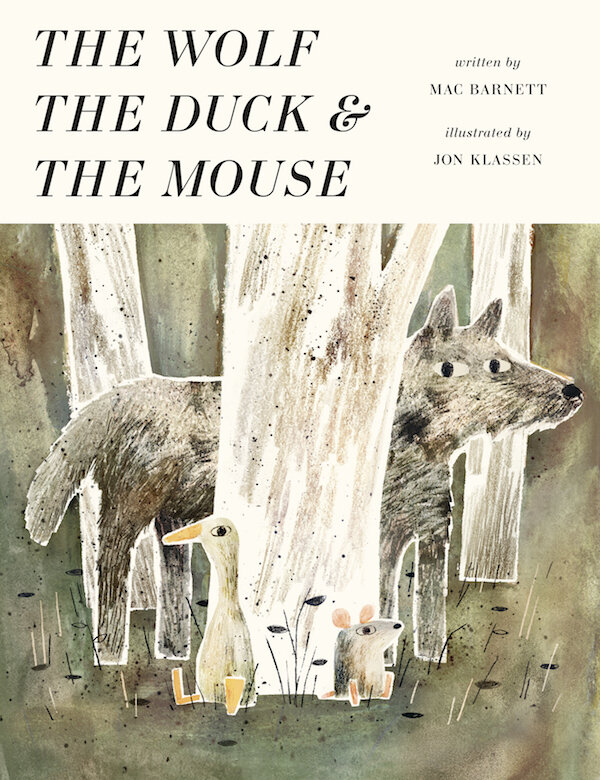

You've said animal characters give you more freedom for writing dialog and can even make drawing easier. Do you plan to use people as characters more in the future?

I think I'll always start with animals as a default. I need a reason for characters to be people instead of animals. Beyond how they talk—meaning, I can have animals talk however I want vs. everyone knows how people talk—there's so much freedom with building a world around animals that I find very useful, as far as where they live and what they worry about. If there were people in this book, you would wonder if they had houses or why don't they just go home? But if they're animals you believe they sleep by this rock. Animals are pretty autonomous. Also, they fit with my idea of conscripting characters into a story. We're always forcing animals to do things, it's how we relate to them, largely. So it makes sense that I would be forcing them to be in my book, where if I thought of people like that, that doesn't work as well.

Beyond the obvious challenges of being a parent and a working creative, are there any surprises that have impacted your work?

I didn't know what to expect from having kids, how it would change the attitude toward my work. At first, it made me go back to my own memories. To see the time the kids take with pages, I think, "Oh that's right. I remember noticing details outside of the main point of the story." I'm not sure it affects my work, but it reinforces how I think about it, and think about being a kid, how I think about time. They are having these whole days with really big experiences. We think they're having these little cute moments, but their day feels huge to them, and that perception is as legitimate as how our day feels to us. Watching the speed of their day, and how strongly they take everything in, what a Big Event is in that day, it's legitimate. It has to be! You have to treat it like that for them. And to treat them like real people, not just potential people who will be people someday. I try to make a book with the attitude that this is for you, today. This is so you have a good time for these twenty minutes and you really like this story. I don't want to make something that they might not understand until later or that feels like an instruction for who they might become. Who they are right now has to be just as valid.

It's almost enough to make you re-evaluate your idea of time. We're supposed to believe time is a relative thing, a perceived thing, but I don't think I really believed it. But now, watching them, watching someone who is feeling how you used to feel about a day, with even small things that mattered a lot, it just tells me that I need to try and bring my brain back to that a little if I'm going to talk to them. You have to treat that idea of time with respect. You need to give smaller moments in books as much thought and weight as if time was as slow as it feels to them, as it is to them.

Is there a ghost story in your future? We learned that your almost-four-year old loves those.

I've been trying for it forever. It's so hard, I love ghost stories so much. A Japanese magazine asked me to do a short story and I drew a really small ghost story that I really liked. The idea was that the ghost wasn't really drawn, it was just negative space in the woods with two eyes, and with a door in the woods that he was walking towards and he goes into the door, and the door closes and he's gone and that's it. I really loved that. I'm trying to do something longer that still leaves lots of room like that. When I was in third grade, the first story I ever wrote was about ghosts who live in a cave. I don't really think our son understands, or I really understood, what ghosts meant in terms of being people who have died. You understand that they're sort of people, but then they're not, that they're in between. Once I think it's going to be a book For My Son though, I want to make it special and I freeze up and can't do anything. Whenever you front load it with whatever it's supposed to mean or who you're going to dedicate it to even, there's more pressure to figure it out. But I'm so glad he likes ghosts. I can tell it gives him a shiver, just on the border of, "Ohhh, I don't know . . . !" but then he wants to go look at it again.

Do you ever do middle or high school events where you talk about illustration or art as a career?

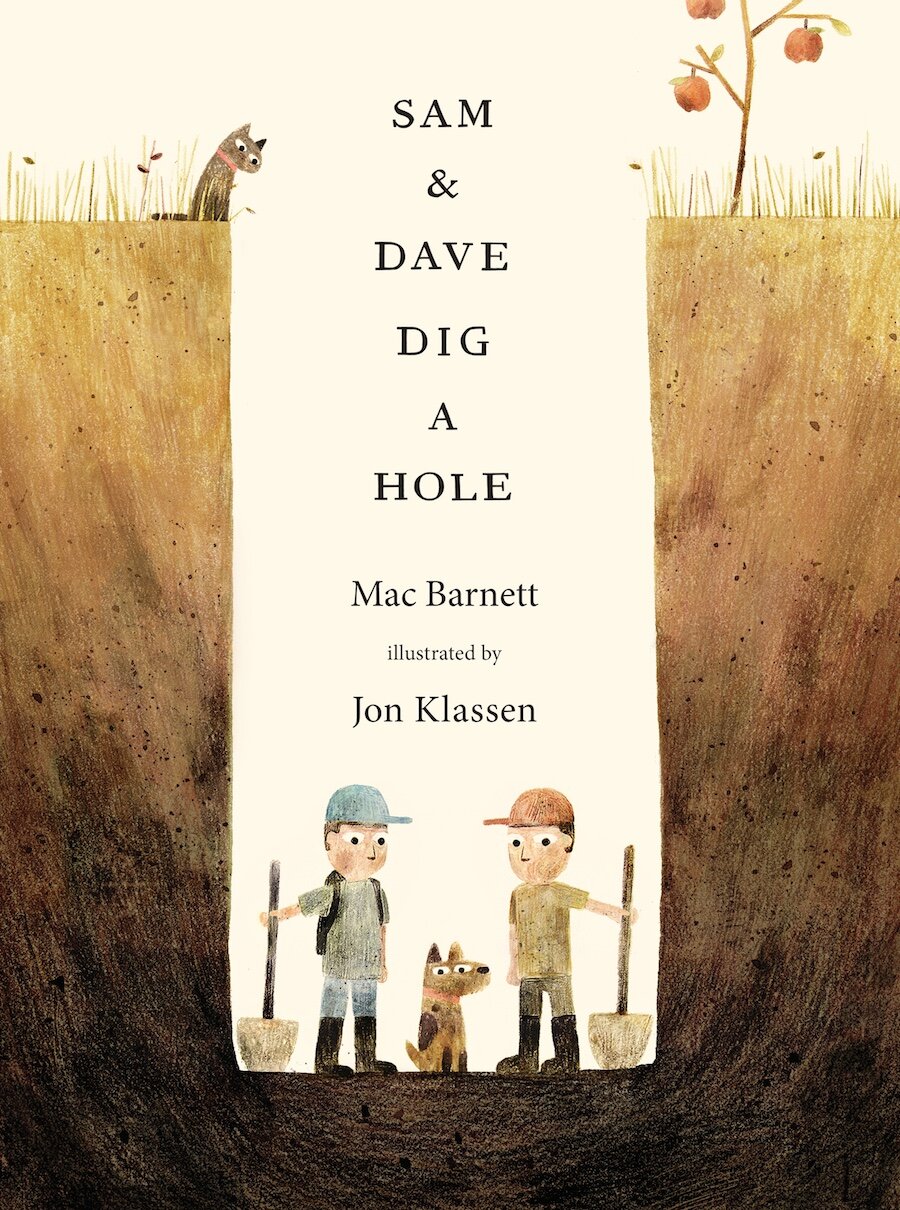

I did one once for a high school art class with Katie [Kate Beaton]. I was going to talk about picture books and she was going to talk about comics. I was excited because I usually talk to little kids so it's different. Here were these almost adults who we could have a real conversation with about career possibilities! But then we got there and we were like "Ohhh, wait, we forgot what high school is like." I think there was one kid smoking, it was just clear no one cared. There was maybe one guy who was interested but didn't want to show that he was. It was a nightmare of getting through the class with everyone texting the whole time. High school really was the worst. Middle school events are easier. It's fun because they still have questions to ask. They're wondering about life in general, about what I do. I like talking to college students because they're really scared about what they're going to do for money in like four months, and I can remember that very clearly. They have technical questions about art that I can relate to, also. I wish I was better at talking to very little kids. It's not my strong suit. I don't dislike it, I really like hanging out with them. But when I tour with Mac [Mac Barnett], it's always so obvious that he's got a gear that he slips into easily where he knows what to say to keep the room of kids interested. I've always had to invent a tone where I'm very stiff and give loud answers that don't quite relate to the question, something to keep it going. It's to distract them from the fact that I don't really know what to say to them.

You said you used some Crayola markers for this book. What is it about them you find intriguing for future projects?

It goes back to what we were talking about with the sky. It's taken me ages to figure this out as an illustrator. It's kind of a technical thing; you'll pick up tools sometimes like pencils or charcoal or whatever and you draw something or do a test for a piece and say: No, I thought this was going to go but maybe I'm just not good at charcoal, it doesn't seem to be going well, it looks like crap. But there are so many variables besides the tool itself. There's the paper, the way you're processing it afterwards, but also there is the size you're working at. I don't know why it took this long, but the idea that tools work differently if I just draw smaller. I realized this specifically looking at Sydney Smith's work. Sydney helped me with my skies a lot. He gave me a step-by-step tutorial over the phone on how to paint one of these sky washes. But he works so small. All of his stuff is so little when he does it and the amount of noise and looseness he gets is so cool and impressive. There is something to the scale he works at that's special. We'd always heard as a standard that you probably should work at about 150% to the size you'll print because that will tighten things up. Sydney is doing the opposite. He's blowing it up. Scanners scan at such high resolution and he's taking full advantage of that. Seeing his results, even though I can't paint like that, but just the amount of noise he gets, is inspiring. So I experimented with these markers, drawing the turtle an inch tall, versus four inches tall. When you draw something that is four inches tall with a marker you end up with lines inside of it that you wouldn't necessarily want, overlaps where you had to fill in or something. You can see the scribbling with a marker because it's so big you had to change course a few times and there's weird overlaps you didn't want. But if you do something smaller with a marker, it feels soft. Everything bleeds together and blends. It has this great quality that I've wanted for a long time, the amount of noise and the vagueness of how it was drawn that I'd been shooting for. So an inexpensive marker has that. And it's not a brush, it doesn't involve water, and it has a pencil-like form that I can control. I can do five little turtles and pick my favorite one. It still feels soft, doesn't feel like hard graphite or sort of etched. When I printed graphite, it felt a little too burnt on the paper. There's something about it that looks overworked, at least how I do it right now. With markers, you can draw the shape you want and you get happy accidents inside the shape that are out of your control.

Did you do your characters in this latest book small or at the classic 150%?

It depended. That was a bit of a trick with the book too. In some of the spreads, particularly that first story, they get small on the page but they start at twice the size. At first, they're about an inch and a half tall but then in the wider spread they get very small. But if you just drew them all at the same size and then shrunk them digitally for the wider spread, you would be able to tell. Your eye can see when you've shrunk it too much, something breaks. Your eye doesn't believe that it was all done that way. Just because you can shrink them down, doesn't mean you ought to and that's been the trick with digital all along. You can do anything. But it doesn't mean it's going to look right . . .

Is there any advice you received from a mentor that you still rely on to keep you creatively challenged?

I had a life-drawing teacher in animation school. We did so much life drawing—for a while it felt like that's all they wanted us to do. Some days, we did eight hours of life drawing, all in two-minute, five-minute poses, some longer ones. I always hated life drawing. I was never good at it and it's one of the more public humiliations because everyone can see what you're drawing, you're up on this easel. You can see what the others got done in three minutes and they can see what you got done. For grading at the end of the year, we would collect our hundreds of newsprint pads and select maybe our thirty best pages. We'd bring them to the teacher and lay them out on the floor and he would wander around and talk with each of us. In my third, and last, year of the program, our teacher was Gerry Zeldin. Everyone said he was considered to be the best, but he didn't really talk much. At my critique, I laid out all my work. I knew I wasn't top of the class or anything but there were a couple in there, maybe just scribbles, that I could convince myself: Maybe I'm an artist! Maybe this is art. Gerry walks around and he's quiet and looks at me and says, "You know, you're never going to be great at this." I'm almost relieved, I say: Yeah, I know! Then he says: Well, we're in third year. What do you want to do? I told him I think I want to do design, like set design (which I did end up doing and I still really enjoy). He replied: So you don't really want to do anything with these anyway. You don't want to animate. I agreed: No, I kind of hate animating. So he said, “Well, then good. Don't worry about it.” It wasn't personal. The way he put it about being uninterested in it versus being crappy at it stuck really hard. Those two things are correlated. Sometimes you're being lazy and not trying and that's why you're not getting any better. But it also has to do with what you are interested in. That's really important information to know about yourself. If you follow your interests you'll get better at the things you're crappy at because broadening is what you need to do. But it has to start with what you're interested in. He wasn't saying I should quit art or something. He was saying, this in particular isn't your thing, you don't seem engaged. And he wasn't saying it as a critique, just stating a fact. That was so important. No one had ever put it like that.

If you're the teacher, your job typically is to help that student get better at whatever it is you're teaching. He didn't seem to feel that way. He was just saying: This isn't your area, or at least it doesn't seem like you want it to be. And I understood that's important too. If I'd really been breaking my heart to be an animator and I really wanted to do this, maybe he would have helped me and said: Well, okay, then let's work on it. But he asked me: Do you care? And I replied: No, I don't think I do. I realized he wasn't being mean to me, he was just being objective. I taught later for a year at CalArts and I wished I could have been more like Gerry, because you do like the teachers who can be bluntly honest with you, in a thoughtful way. His attitude has always stuck with me.

I wasn't used to Gerry's style of teaching because I think a lot of teachers in the arts realize they are managing feelings as much as they are managing skills. They step lightly because these things are so connected. Your work is connected to your picture of yourself and who you think you are and who you want to be. So a critique about it isn't just about did you draw this car properly, it's you're a terrible person because this drawing is bad. That's how you take it when you're twenty-two. But Gerry gave me the benefit of the doubt: You can take hearing this. This isn't going to break you. You're just not going to be great at this. That benefit of the doubt to the student, looking at them straight. I'd never had an experience like that before.

Klassen’s studio

The start of your career was in animation. Do you have an interest in returning to this medium as well as continuing to create picture books?

Yeah, I do. I miss working with a team and the results that gives. I was never involved in writing for animation, I was always working on someone else's project. But that was fun too, being a technician on someone else's project was really freeing. I learned a lot. What attracted me to books was the speed, how fast they were done, relative to a film, anyway. Everything in animation, at least in feature animation, takes forever, four years to make a movie. It was fun to watch these big studios put these movies out with such scale, where it goes out to the whole world. It was really exciting. But as soon as you do a book and it takes eight months to come out . . . I can get a whole idea off my table that fast. And the more I worked at the studios, the more I found out that, for better and worse, I had impulses and idiosyncrasies of my own that were getting louder, and the fact that I didn't have to check with forty people before I pull the trigger on an idea got to be more attractive. But animation is still so fun. There's nothing quite like watching something you did move around and have music to it. It's pretty addictive. You have to be careful. With animation projects, I'm aware they can swallow a lot of my time. And I have books to do! But it doesn't feel unrealistic that I would get back into it somehow. I hope so. But I don't think I would ever leave the books behind completely to do it. I like them too much, and there's still too much mystery in them for me.

Great! That's good to hear.

I hope so!

Thanks, Jon, for visiting with us again, sharing this book and so much of what goes into your process!

For more on Jon Klassen:

For earlier interviews with Klassen:

Interview with Jon Klassen and Mac Barnett

Interview with Jon Klassen

All images used with permission by Jon Klassen and Candlewick Press.

The Rock from the Sky. © 2021 by Jon Klassen. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Candlewick Press, Somerville, MA