An Interview with Dušan Petričić

Dušan Petričić

January 31, 2015

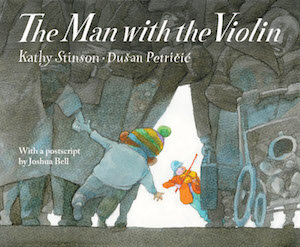

Dušan Petričić is the award winning illustrator (and upcoming first time author) of children's books. He is the winner, with author Kathy Stinson, of Canadian Children's Book Centre top award for 2014, the TD Canadian Children's Literature Award, for The Man with the Violin. Petričić has illustrated dozens of children's books, including In the Tree House (a finalist for the same award) , Mattland and My Family Tree and Me. His editorial illustrations have appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and Toronto Star.

A Selection of Work

Do you still travel back and forth between Belgrade and Toronto?

Yes, I do. Right now I'm more in Belgrade, but I also travel to Toronto for the publishers.

For twenty years, I worked for the Toronto Star. From time to time I still do some illustrations for them, but I am not working for them as I did.

Do you miss doing editorial cartoons?

I'm not missing it because I am doing exactly the same thing here in Belgrade, for the newspaper, every Sunday. It's the biggest newspaper in Serbia, called Politika. I always find a way to express my political feelings. I enjoy that.

And when I am full with politics, I have the way to escape to a children's world and vice versa. So I share my time between political editorial cartoons and children's illustration.

You drew a lot as a young child. Did you draw your surroundings, people or from your imagination?

I did a little bit of everything, as kids usually do. I did do portraits, of course, but also I liked to draw animals, as a very young kid. Later, when I was ten or twelve, I tried to imitate comic strips, as a game. Then I started to work a little more seriously. I tried to draw some nature landscapes. But all that time I continued to do portraits and people, which was my preoccupation all those years.

Only with people is there a different level, a psychology. I love psychology. To draw expressions of the face, the eyes. That's always a great challenge for me.

Cover of The Man with the Violin, by Kathy Stinson, illustration by Dušan Petričić

We love the expression you put into the faces of the characters in your picture books. In the award-winning The Man with the Violin you added so much to the words through your illustration.

I find that important, particularly when you're working for kids. They love that, to see certain expressions. Again, that's something that I’m doing the same way for the political cartoons. Psychology and expressions. That’s important everywhere, for kids as well as grown-ups. They love to see when you draw a funny expression on the face. Half of your job is done, if you do that the proper way.

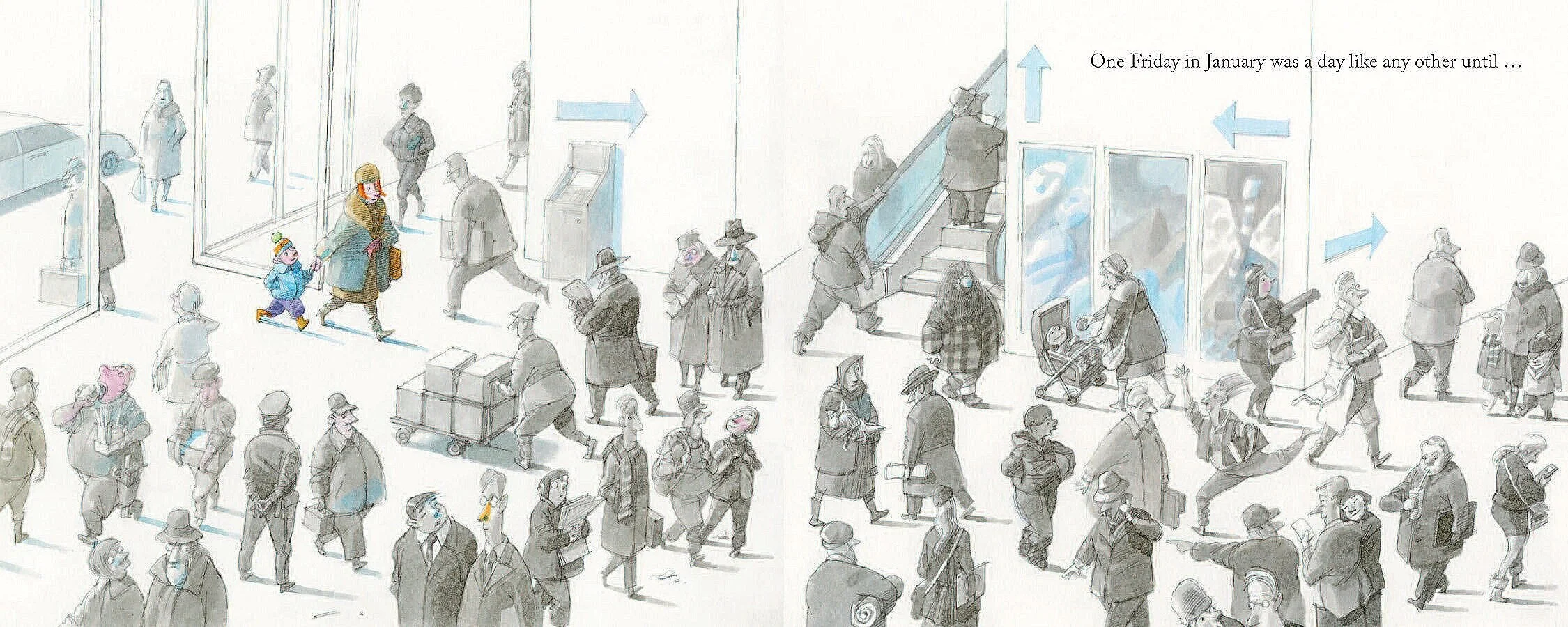

Interior spread from The Man with the Violin, by Kathy Stinson, illustration by Dušan Petričić

The author describes how the boy notices things and his mother does not. You created a wonderful illustrated stream of the boy’s thoughts in contrast to the mother’s blank thought stream. How did you come up with that idea?

I'm sure you remember that when you were a kid, there was a lot of things you saw around yourself, that your parents or adult people didn't see. I have four children and six grandchildren. So I spend a lot of time with young people and I am always observing how they react to things. I learn from that.

In that book, there's a lot of funny faces to see. I'm sure that the best part of my books always is the humor. There is a little bit of humor everywhere. Kids love to laugh, love to enjoy funny things. That's why I always introduce humor in my illustrations for kids.

Interior spread from The Man with the Violin, by Kathy Stinson, illustration by Dušan Petričić

Some authors and illustrators try hard to teach kids, to pass knowledge to them. We love when that can be done with humor.

It is the way to reach kids’ souls. Through the humor, absolutely.

You taught illustration and book design for many years. Do you still teach?

Not regularly, not now. Though from time to time I do. For example, soon I am going to my Academy of Arts, here in Belgrade, to talk with the students about illustration, books and to share my experience, my years with them.

What did you enjoy most about your teaching experience?

The best thing about the teaching experience is that you're working with young people, definitely. Young people are always a huge inspiration for artists. This is the most important thing — the communication with young people. The second thing is the great pleasure, when you are teaching young people, that you can see in them (if, of course, they understand what you are talking about) the huge advance in their way of thinking, in receiving and accepting the world around themselves. That's a huge thing for me, to see that I do help them see the world better.

In an interview, you told kids you always keep a pencil handy, tucked into your shirt. Do you keep an ongoing sketchbook? Do you jot down ideas or things from your imagination?

No, no, I don’t. The pencil that I keep with me, that is true. But it is only if I have to note something. But I'm not making sketches, like artists did a hundred years ago.

So you don't keep a sketchbook with you . . .

Oh, no, no. I keep it in my mind, in my brain. And when I go home, into my studio, then I try to realize, to put on paper, what is smart and not smart, that I can do.

Cover of In the Tree House, by Andrew Larsen, illustration by Dušan Petričić

You have said your advice to young artists is to “Think, think, think, then draw.”

Yes, that's been my personal experience from working in cartoons and illustration. I did a lot of thinking first. Always I do a lot of thinking. Hours and hours sometimes . . . while trying to reach the best possible solution, the best possible idea. And then I take a pencil and paper.

I saw students, particularly very young students, do this: as soon as you give them an item to draw, they immediately, seconds after that, they start to put something on paper. And I would tell them, “No, no! Please don't do that first. Wait at least two days before you put any line on your paper!” It is very important.

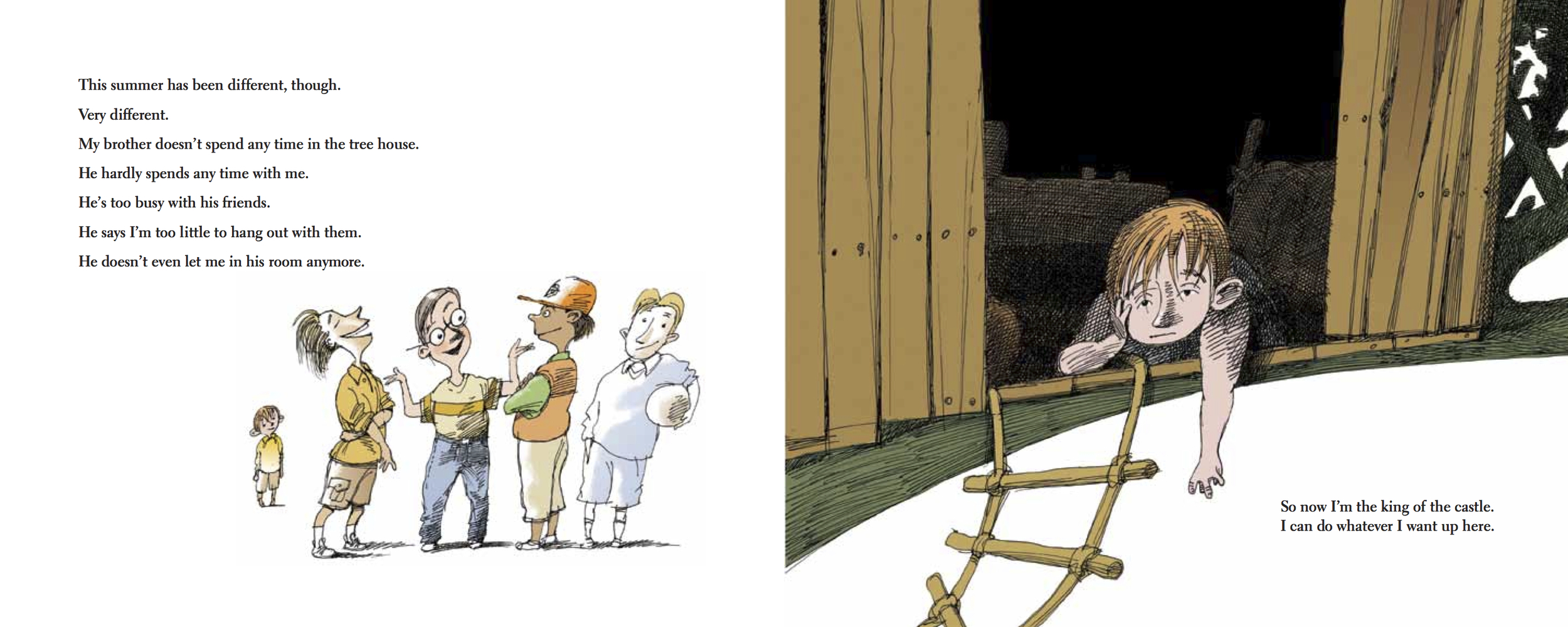

Interior spread from In the Tree House, by Andrew Larsen, illustration by Dušan Petričić

Interior spread from In the Tree House, by Andrew Larsen, illustration by Dušan Petričić

Interior spread from In the Tree House, by Andrew Larsen, illustration by Dušan Petričić

When I started teaching in Toronto, years ago at Oxford College, I went for the first time to the classroom and I brought fortune cookies with me. You know fortune cookies? You break it and you find a little piece of paper with a few words. Which usually means something very smart, some advice. Those sentences are precise, focused on a single idea, with these few words. These are a good exercise on how to translate that idea into a drawing, a visual message. So I gave them the cookie and they read it. I said, "Okay, illustrate that for me,” and they would take the paper immediately and start drawing! How can they do that? Before you think what this sentence means! This is why I insist on that.

If you think just a few minutes, you can see that it is a very clear and simple message. What is the important piece, to make more than one idea, to actually force them to think more. Don't be settled with the first idea. Because usually the second or third or fourth idea is much better than the first one.

That’s a creative exercise. Did you get some good results from your students?

Sometimes, yes. Sometimes, no. And sometimes I found that they got a very difficult sentence, very hard to illustrate and then I would give them another cookie!

Interior spread from In the Tree House, by Andrew Larsen, illustration by Dušan Petričić

You have expressed your concerns about presenting a sweetened, idealized portrayal of childhood in picture books.

Yes, I discovered, looking at my children and their children and young people, that they are reading beautiful, nice books that I read also years ago. But suddenly, when you are eighteen, and you open the door of real life you understand what you have learned before is ninety percent lying. It's not real life. I felt guilty! In trying to explain political cartoons through my illustrations to adult people, I am trying to repair some damages that I maybe have done with the illustrations for children.

A Dangerous Engine: Benjamin Franklin, from Scientist to Diplomat, by Joan Dash, illustration by Dušan Petričić

For that reason, do you lean toward illustrating stories or books like The Man with the Violin about a real person, rather than purely fictional stories?

I can say precisely that I love illustrating books with some kind of challenge. When it looks from the very beginning like it's not easy to illustrate, that's a huge challenge for me and then I am going to pick that text or story. Yes, I love to illustrate, from time to time, stories like . . . you mentioned the book on Benjamin Franklin, I love to illustrate real people, real-life stories.

We know that illustrators typically don't have contact with the author. Are you comfortable with that or do you wish there was more interaction?

I am absolutely comfortable with it. I wouldn't like to talk to a writer, because a writer always has some specific ideas about what they wrote. I consider myself a first reader of the text. As the first reader I'm going to come up with some ideas. If you follow the story from the writer’s head, then you follow his idea, which is not necessarily the right one for you, as an artist. It happens to me that I often come up with some additional ideas and the stories are made richer with that. Picture books are a combination, a mixture of words and pictures.

At the beginning, I like not to be overwhelmed by a writer's ideas, their ideas about the text. I am the reader. I am going to read the text and then let me show you what I discover in your text. That's how it works.

After you have come up with your concepts, have you had either the writer or the editor come back to you and suggest any changes?

Almost never. Maybe for the details, when I would take their suggestions. But after years and years, I understand very well what the writers want to say and and what publishers want to publish. It works in a proper way, I believe.

Cover of Mattland, Hazel Hutchins and Gail Herbert, illustration by Dušan Petričić

Your authors seem to be charmed by the touches that you add to their text. It seems to be a collaboration that's working well.

Yes, it works really well. Every writer remembers something from their own childhood. And as an illustrator, I do the same thing. Actually all childhoods are similar. We live in a specific world for a few years, it just depends on which country you are living in at the time. With all our ideas, coming from that place, it is not a big problem to get to a solution.

What happens when you illustrate, and you offer the book to kids to read with the illustrations, you influence the brains of young kids. When they see something that I draw, they accept that as a final thing. It might not be the final thing. Actually it might be that kids can have a different idea about what they see than what their brain sees for that text.

Interior spread from Mattland, Hazel Hutchins and Gail Herbert, illustration by Dušan Petričić

So I finally thought of an extreme solution. Maybe the best book for kids would be if they have the spread with text and an empty page facing it. He could put his own illustrations . . it might be very interesting. Give that kind to ten or twenty kids and then pick it up and see how they saw the text. That might be a good test, an interesting experiment.

Interior spread from Mattland, Hazel Hutchins and Gail Herbert, illustration by Dušan Petričić

You’ve said that, growing up in Belgrade, you liked to pretend that you had grown up across the river, in an older town. What about that town intrigued you as a child?

That's true. Now that area is part of the city of Belgrade. At that time it was a smaller city and it had everything that I think is necessary for a nice childhood. One small hill, one old tower on top of the hill, one graveyard and there was a huge river behind that and small parks. So everything you need to have the best and nice childhood.

Interior spread from The Man with the Violin, by Kathy Stinson, illustration by Dušan Petričić

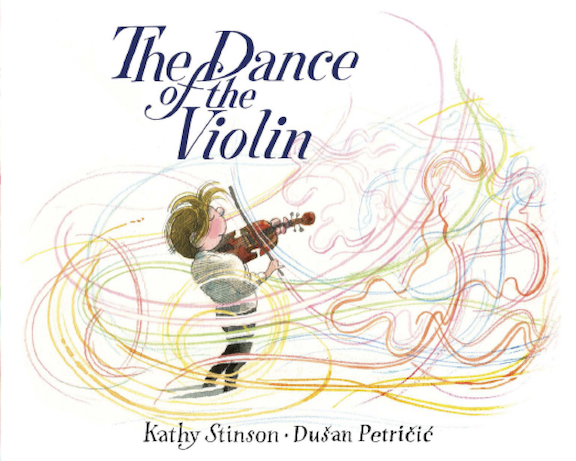

In The Man with the Violin, you beautifully captured the idea of being overtaken by music. Do you play a musical instrument?

No, unfortunately not. I do not play. I do not sing. I am an appreciator!

The most important thing for me, with the visual in that particular book, was how to transfer the feeling of one art to another, in this case, the music. That is always a good challenge for me.

What are some of your favorite books from your own childhood?

The most important book from my childhood was The Boys from Pavel Street, by Hungarian author Ferenc Molnár. That's an amazing, a beautiful book. I have met, in my life, hundreds of men who grew up with that book. It is particularly a boy’s book, of course, about a group of kids in Budapest in the beginning of the 20th century. It was a novel with a few illustrations. But I was not influenced with the visual view of those things. I had my own ideas in my head about how they would look.

But as a boy I had one encyclopedia. It was a very small encyclopedia, a very old one, with beautiful black and white linear drawings, life-like drawings of everything that you were surrounded with. I grew up with that book. It was an important book for me. The way that I do my illustrations today mostly comes from that experience. I loved as a kid to lay on the floor, to take some sweets with me, and to look at that book, page by page. So I must say that I really grew up with the book that in some way influenced my professional work for years and years after that.

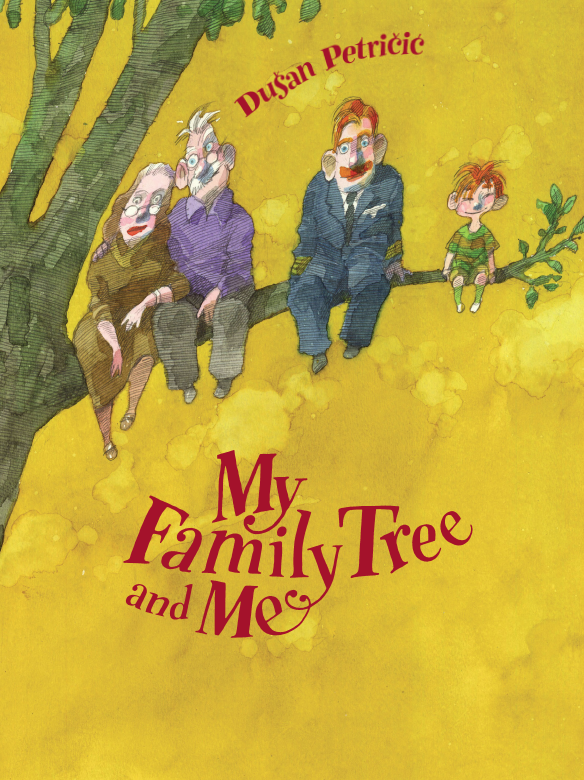

Front and back covers of My Family Tree and Me, Dušan Petričić

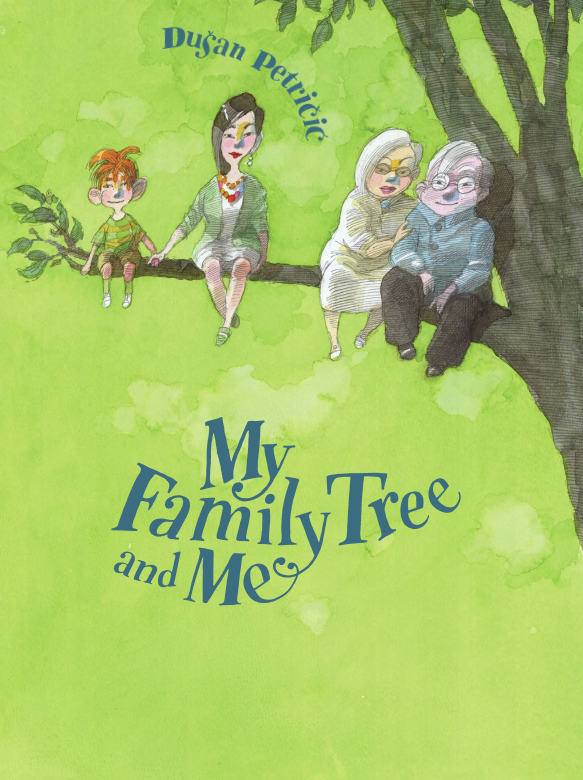

Interior spread from My Family Tree and Me, Dušan Petričić

Interior spread from My Family Tree and Me, Dušan Petričić

Have you ever been interested, after years of illustrating other people’s work, in writing a children's book?

Yes, actually I just did one. It is the first one. It will be published by Kids Can Press in Toronto. It's actually a version of book I did years ago, while I was in Serbia. It's a story about a family tree, My Family Tree and Me. That's the book I wrote—short text, of course, mostly visual. So. The first one! Of course I have had the idea for years to start doing that kind of books and have had ideas for some particular books. And I am preparing to start this now, right now.

Cover of InvisiBill, by Maureen Fergus, illustration by Dušan Petričić

You also have a new picture book coming out soon titled InvisiBill?

Yes, it's an interesting story and I found a very specific way of illustrating it conceptually.

Interior spread from InvisiBill, by Maureen Fergus, illustration by Dušan Petričić

Do you have any preliminary sketches from your books? Preliminary to the final published piece . . .

I have some of those. Not for all the books. I do have something interesting. I have to dig it from my boxes!

Preliminary sketch by Dušan Petričić for cover of The Color of Things

Preliminary sketch by Dušan Petričić for cover of The Color of Things

Preliminary sketch by Dušan Petričić for cover of The Color of Things

Preliminary sketch by Dušan Petričić for cover of The Color of Things

Final cover by Dušan Petričić of The Color of Things

It is always interesting to see the artist's work that comes before the final published piece.

The first book I illustrated when I came to Canada was The Color of Things for Rizzoli in New York. I did the illustrations in Toronto and sent them by FedEx to New York. Because at that time, we didn't have the Internet. So when I made the sketches for the book, all the sketches, the whole book they accepted immediately. Without any detail that they would like to change. But when I said that here is the cover page, they instantly phoned and said, “Yeah, that's nice but . . . but it would be nice if you could change it. If you could send another sketch for us?” I had some other ideas, so again I made three sketches, trying to persuade them to accept one of my sketches. And they again said, “Ah, yeah, that is nice, but, well, let's say, is that the best?” In short, I made thirteen cover sketches.

I wanted to tell them, “No, don't go with this one!” Finally, I made a mixture, which I liked less than the sketches that I had sent to them. The final one was actually their idea. So, for the first time, I understood that the final word about illustrations that go into the book comes from the editors. But talking about the cover, the final word belongs to the marketing department of the publisher. They always know the best one or what will sell the book.

So when I started in Canada and North America I wanted to show them a lot of ideas, but then very soon I saw that they don't know what to do with so many ideas. So I started to send one or two. There, now you can get one. Just pick one!

By this time they probably don't give you much pushback on any of your work.

Yes, I'm experienced enough. They know that and I know how it all works. So it works well now.

Do you ever do any art just for your own interest?

No, I don't have any time for this. I think 99.9% of my art is published somewhere.

That's impressive.

Yes. I'm very fortunate that it is that way.

For the book My Toronto (not a children's book) you said you were able to offer a multi-dimensional perspective because you were an immigrant and not a native Canadian. Even with picture books, do you think that has informed your work?

At the very beginning, I used to illustrate books for Canadian and North American publishers. I think I needed one year to learn exactly how it works. There are some things that are different there than in Europe—communication with kids and between publishers and readers, so I had to learn a few things. It wasn't so difficult, of course. But with that book, My Toronto, I think the most important thing is that when you come to another country, to another society, to another city, as an outsider, you see more things than somebody who is living there and has spent every day, years and years in that city. So that was something that for me was very important. I believe in the final result it is visible. I am someone who sees things differently than people who lived there for thirty or more years. And some part of that I include in my work on children’s books, some of the experiences which I have brought with me from other cultures and other societies.

Have your political cartoons in Serbia been affected by the years you spent in Canada?

Yes, definitely. It is always a two-way situation. When I came to Canada I brought with me some experiences from living in a socialist country, the different historical facts. And now, after twenty years living in North America, I brought a lot of things, very useful things, back to my country. So, the mixture, it is always very good, the different points of view.

What brought you to Canada originally? Why Toronto?

I actually never dreamt about that, to leave my country. I loved to travel but not to live in another country. But it was a very difficult time in Serbia. There was war and the political situation . . . I decided to try and help my family to live in a different way. That was the first reason. The reason for: why Canada? I have an older brother who at that point had lived in Toronto for almost 35 years, so it was easier to get papers for Toronto.

Were you ever tempted to move to New York, with all the activity in your field and with so much publishing there?

I thought about that. But after a while, I understood that first, New York was more expensive than Toronto, as a city. So you need to work even more in order to live in New York! And the second thing is that Toronto was not too far from Europe and actually easy for me to work with European publishers and Toronto publishers.

But, I must say that New York is actually a more exciting city than any city in the world. That would be the number one place I would like to live in the world, if not here in Belgrade.

Do you ever reach a point in doing illustration when you realize you shouldn't do anything more to it, that you have reached the sweet spot where you are done. And this is the very best that you're going to be able to do for that particular image.

Sometimes, yes. Sometimes then I try to stop at that point. Only if I'm where I feel like it is finished enough to be understandable. Sometimes, very often, I must say I'm not satisfied and if I finish completely after two or three days, I have forced myself (years ago I started with that practice) to destroy immediately the drawing. If I leave it for another day, I might leave it too long and then I'm not going to be happy with that. So if I'm not happy, I destroy it immediately.

Not easy, always, but I think it is important.

In the Tree House, by Andrew Larsen, illustration by Dušan Petričić

Do you start in pencil and then ink and then apply color?

Yes. And now, in spite of the fact that I don't like computers and Photoshop, I must say it's a very simple thing to finish something and to communicate with the publisher in another part of the world, so I have to use the computer. Sometimes I make my illustrations in black-and-white, then I scan them, and add color in Photoshop. But still, using the colors of colored pencils, particularly for picture books, is better than using the colors just from the computer.

Have you ever considered using other media?

Actually not. As a very young kid, when I started to be interested in visual arts, I started with oil painting. Not very successfully! I was too young. But now, from all those years and my experiences, I have found the right media for myself and I don't want to change it.

Are there any current authors writing picture books for whom you would like to do illustration?

There is one writer that I am just discussing, with his publisher, for the last two years actually, trying to do the book, together. This author is a poet, Dennis Lee. It is very different illustrating poems and I am looking forward to doing another book or two in the future.

I love poetry. I think it is the most important field in literature for me. With poetry you have to be very precise, very focused and explain simple things. There's always something a little bit conceptual in each poem. So I love to do that. It's a lot to do with my opinion about cartoons in general, not only political cartoons. The cartoon is a way of thinking. So poetry and cartoons are similar to me. And that similarity is very simplistic, with the concept of how to find the right, the most precise way to explain yourself. With the least possible words.

That's a perfect description of your fortune cookie exercise that you used with your illustration students.

You are right. That's true!

We appreciate the time you spent with us in reflecting on your work.

My pleasure.

A Selection of Petričić’s work

Images from The Man With the Violin © 2013, by Kathy Stinson/ © 2013 Dušan Petričić (illustrations), and Mattland, © 2008 by Hazel Hutchins and Gail Herbert/© 2008, Dušan Petričić (illustrations), published by Annick Press Ltd. are used by permission of Annick Press Ltd.

Images from In The Tree House, © 2013 by Andrew Larsen, © 2013 illustrations by Dušan Petričić, and My Family Tree and Me, by Dušan Petričić, illustrations by Dušan Petričić are used by permission of Kids Can Press.